- •Contents

- •Preface to the first edition

- •Flagella

- •Cell walls and mucilages

- •Plastids

- •Mitochondria and peroxisomes

- •Division of chloroplasts and mitochondria

- •Storage products

- •Contractile vacuoles

- •Nutrition

- •Gene sequencing and algal systematics

- •Classification

- •Algae and the fossil record

- •REFERENCES

- •CYANOPHYCEAE

- •Morphology

- •Cell wall and gliding

- •Pili and twitching

- •Sheaths

- •Protoplasmic structure

- •Gas vacuoles

- •Pigments and photosynthesis

- •Akinetes

- •Heterocysts

- •Nitrogen fixation

- •Asexual reproduction

- •Growth and metabolism

- •Lack of feedback control of enzyme biosynthesis

- •Symbiosis

- •Extracellular associations

- •Ecology of cyanobacteria

- •Freshwater environment

- •Terrestrial environment

- •Adaption to silting and salinity

- •Cyanotoxins

- •Cyanobacteria and the quality of drinking water

- •Utilization of cyanobacteria as food

- •Cyanophages

- •Secretion of antibiotics and siderophores

- •Calcium carbonate deposition and fossil record

- •Chroococcales

- •Classification

- •Oscillatoriales

- •Nostocales

- •REFERENCES

- •REFERENCES

- •REFERENCES

- •RHODOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Cell walls

- •Chloroplasts and storage products

- •Pit connections

- •Calcification

- •Secretory cells

- •Iridescence

- •Epiphytes and parasites

- •Defense mechanisms of the red algae

- •Commercial utilization of red algal mucilages

- •Reproductive structures

- •Carpogonium

- •Spermatium

- •Fertilization

- •Meiosporangia and meiospores

- •Asexual spores

- •Spore motility

- •Classification

- •Cyanidiales

- •Porphyridiales

- •Bangiales

- •Acrochaetiales

- •Batrachospermales

- •Nemaliales

- •Corallinales

- •Gelidiales

- •Gracilariales

- •Ceramiales

- •REFERENCES

- •Cell structure

- •Phototaxis and eyespots

- •Asexual reproduction

- •Sexual reproduction

- •Classification

- •Position of flagella in cells

- •Flagellar roots

- •Multilayered structure

- •Occurrence of scales or a wall on the motile cells

- •Cell division

- •Superoxide dismutase

- •Prasinophyceae

- •Charophyceae

- •Classification

- •Klebsormidiales

- •Zygnematales

- •Coleochaetales

- •Charales

- •Ulvophyceae

- •Classification

- •Ulotrichales

- •Ulvales

- •Cladophorales

- •Dasycladales

- •Caulerpales

- •Siphonocladales

- •Chlorophyceae

- •Classification

- •Volvocales

- •Tetrasporales

- •Prasiolales

- •Chlorellales

- •Trebouxiales

- •Sphaeropleales

- •Chlorosarcinales

- •Chaetophorales

- •Oedogoniales

- •REFERENCES

- •REFERENCES

- •EUGLENOPHYCEAE

- •Nucleus and nuclear division

- •Eyespot, paraflagellar swelling, and phototaxis

- •Muciferous bodies and extracellular structures

- •Chloroplasts and storage products

- •Nutrition

- •Classification

- •Heteronematales

- •Eutreptiales

- •Euglenales

- •REFERENCES

- •DINOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Theca

- •Scales

- •Flagella

- •Pusule

- •Chloroplasts and pigments

- •Phototaxis and eyespots

- •Nucleus

- •Projectiles

- •Accumulation body

- •Resting spores or cysts or hypnospores and fossil Dinophyceae

- •Toxins

- •Dinoflagellates and oil and coal deposits

- •Bioluminescence

- •Rhythms

- •Heterotrophic dinoflagellates

- •Direct engulfment of prey

- •Peduncle feeding

- •Symbiotic dinoflagellates

- •Classification

- •Prorocentrales

- •Dinophysiales

- •Peridiniales

- •Gymnodiniales

- •REFERENCES

- •REFERENCES

- •Chlorarachniophyta

- •REFERENCES

- •CRYPTOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Ecology

- •Symbiotic associations

- •Classification

- •Goniomonadales

- •Cryptomonadales

- •Chroomonadales

- •REFERENCES

- •CHRYSOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Flagella and eyespot

- •Internal organelles

- •Extracellular deposits

- •Statospores

- •Nutrition

- •Ecology

- •Classification

- •Chromulinales

- •Parmales

- •Chrysomeridales

- •REFERENCES

- •SYNUROPHYCEAE

- •Classification

- •REFERENCES

- •EUSTIGMATOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCES

- •PINGUIOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCES

- •DICTYOCHOPHYCEAE

- •Classification

- •Rhizochromulinales

- •Pedinellales

- •Dictyocales

- •REFERENCES

- •PELAGOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCES

- •BOLIDOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCE

- •BACILLARIOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Cell wall

- •Cell division and the formation of the new wall

- •Extracellular mucilage, biolfouling, and gliding

- •Motility

- •Plastids and storage products

- •Resting spores and resting cells

- •Auxospores

- •Rhythmic phenomena

- •Physiology

- •Chemical defense against predation

- •Ecology

- •Marine environment

- •Freshwater environment

- •Fossil diatoms

- •Classification

- •Biddulphiales

- •Bacillariales

- •REFERENCES

- •RAPHIDOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCES

- •XANTHOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Cell wall

- •Chloroplasts and food reserves

- •Asexual reproduction

- •Sexual reproduction

- •Mischococcales

- •Tribonematales

- •Botrydiales

- •Vaucheriales

- •REFERENCES

- •PHAEOTHAMNIOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCES

- •PHAEOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Cell walls

- •Flagella and eyespot

- •Chloroplasts and photosynthesis

- •Phlorotannins and physodes

- •Life history

- •Classification

- •Dictyotales

- •Sphacelariales

- •Cutleriales

- •Desmarestiales

- •Ectocarpales

- •Laminariales

- •Fucales

- •REFERENCES

- •PRYMNESIOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Flagella

- •Haptonema

- •Chloroplasts

- •Other cytoplasmic structures

- •Scales and coccoliths

- •Toxins

- •Classification

- •Prymnesiales

- •Pavlovales

- •REFERENCES

- •Toxic algae

- •Toxic algae and the end-Permian extinction

- •Cooling of the Earth, cloud condensation nuclei, and DMSP

- •Chemical defense mechanisms of algae

- •The Antarctic and Southern Ocean

- •The grand experiment

- •Antarctic lakes as a model for life on the planet Mars or Jupiter’s moon Europa

- •Ultraviolet radiation, the ozone hole, and sunscreens produced by algae

- •Hydrogen fuel cells and hydrogen gas production by algae

- •REFERENCES

- •Glossary

- •Index

DINOPHYTA 303

there can be a slight difference in the size of the gametes. The cells are joined together by a hyaline globular bridge slightly below the intersection of the transverse and posterior grooves. After 30 minutes the fusion of protoplasts has begun, with the bridge between the two cells enlarging. At the end of fusion a cell similar to a vegetative cell is attained. The flagella and nuclei of each gamete are still distinct. The zygote grows, at first having the shape of a vegetative cell, and later the epicone elongates. One of the transverse flagella is lost during this development, but both of the posterior flagella persist. The non-motile zygote suddenly rounds off and secretes a preliminary wall. This wall is subsequently inflated, giving rise to a hyaline area between the wall and the protoplast surface. An ornamentation of small separated granules now appears on the protoplast wall, which grow out radially to become spines while the hyaline area increases in width. The preliminary wall then bursts and crumples away to one side of the spore. The preliminary wall is necessary for formation of the hypnospore. The duration of the preliminary wall is only about 9 minutes.

During the next 48 hours the hypnospore matures, with the plastids bleaching and becoming inconspicuous, masses of red oil appearing, the starch becoming indistinct, and the two nuclei now fusing. A thick cellulosic endospore is also secreted under the exospore with its spines. The hypnospores germinate after treatment for 4 weeks in the dark at 3 °C before being returned to light and higher temperature. After the cellulosic endospore has been digested away, approaching release of the swarmer is indicated by a slight contraction of the protoplast so that the transverse groove of the prospective flagellate becomes visible. The space between the spore wall and the surface of the swarmer is filled with mucilage. Eventually the wall bursts, and the swarmer escapes, enveloped in mucilage. The swarmer frees itself from the mucilage and swims away. The swarmer is rather plump and of oval shape at first, and, apart from red oil globules, nearly colorless; but later it acquires brown pigment, and its form becomes similar to that of the vegetative cell. Two “skiing track” posterior flagella have reappeared. The swarmer then goes through two meiotic divisions, resulting in four haploid flagellates.

Fig. 7.60 Hans Adolf von Stosch, 1908–1987. Dr. von Stosch was born in Berlin and studied at the Universities of Kiel, Gottingen, and Munich. Before World War II he worked at the University of Konigsberg/ Ostppreussen. He became a soldier in 1939, was taken prisoner in Tunisia in 1943, and was released in England in 1947. He obtained a position at the Technical University in

Darmstadt, where he began his studies on algae in earnest. In 1955, he moved to the University of Marburg where he stayed until his retirement in 1976. His work on the life histories of dinoflagellates is some of the best work done on the group. (Photo from Garbary and Wynne, 1996.)

REFERENCES

Abrahams, M. V., and Townsend, L. D. (1993). Bioluminescence in dinoflagellates: a test of the burglar alarm hypothesis. Ecology 74:258–60.

Adamich, M., Laris, P. C., and Sweeney, B. M. (1976). In vivo evidence for a circadian rhythm in membranes of Gonyaulax. Nature 261:583–5.

Baillie, B. K., Belda-Baillie, C. A., and Maruyama, T. (2000). Conspecificity and indo-pacific distribution of Symbiodinium genotypes (Dinophyceae) from giant clams. J. Phycol. 36:1153–61.

304 CHLOROPLAST E.R.: EVOLUTION OF ONE MEMBRANE

Balzer, I., and Hardeland, R. (1996). Melatonin in algae and higher plants – possible new roles as a phytochrome and antioxidant. Bot. Acta 109:180–3.

Barlow, S. B., and Triemer, R. E. (1988). The mitotic apparatus of the dinoflagellate Amphidinium carterae. Protoplasma 145:16–26.

Berdach, J. T. (1977). In situ preservation of the transverse flagellum of Peridinium cinctum (Dinophyceae) for scanning electron microscopy. J. Phycol.

13:243–51.

Bibby, B. T., and Dodge, J. D. (1972). The encystment of a freshwater dinoflagellate: A light and electronmicroscopical study. Br. Phycol. J. 7:85–100.

Bouck, G. B., and Sweeney, B. M. (1966). The fine structure and ontogeny of trichocysts in marine dinoflagellates. Protoplasma 61:205–23.

Bricheux, G., Mahoney, D. G., and Gibbs, S. P. (1992). Development of the pellicle and thecal plates following ecdysis in the dinoflagellate Glenodinium foliaceaum. Protoplasma 168:159–71.

Brooks, B. J., and Anderson, D. M. (1990). Biochemical composition and metabolic activity of Scrippsiella trochoidea (Dinophyceae) resting cysts. J. Phycol. 26:289–98.

Burkholder, J. M., and Glasgow, H. B. (1997). Trophic controls on stage transformation of a toxic ambushpredator dinoflagellate. J. Euk. Microbiol. 44:200–5.

Buskey, E. J., and Swift, E. (1983). Behavioral responses of Acartia hudsonica to simulated dinoflagellate bioluminescence. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 77:43–58.

Cembella, A. D. (2003). Chemical ecology of eukaryotic microalgae in marine ecosystems. Phycologia 42:420–47.

Chapman, D. V., Dodge, J. D., and Heaney, S. J. (1982). Cyst formation in the freshwater dinoflagellate

Ceratium hirundinella. J. Phycol. 18:121–9. Chatton, E. (1952). Classe des dinoflagelles ou peri-

diniens. In Traité de Zoologie, ed. P-P. Grassé, pp. 304–406. Paris: Masson.

Chinain, M., Germain, M., Sako, Y., Pauillac, S., and Legrand, A-M. (1997). Intraspecific variation in the dinoflagellate Gambierdiscus toxicus (Dinophyceae). I. Isoenzyme analysis. J. Phycol. 33:36–43.

Clarke, K. J., and Pennick, N. C. (1976). The occurrence of body scales in Oxyrrhis marina Dujardin. Br. Phycol. J. 11:345–8.

Crawford, R. M., Dodge, J. D., and Happey, C. M. (1970). The dinoflagellate genus Woloszynskia. I. Fine structure and ecology of W. tenuissima from Abbot’s Pool, Somerset. Nova Hedwigia 19:825–40.

Daugbjerg, N., Hansen, G., Larsen, J., and Moestrup, O. (2000). Phylogeny of some major genera of

dinoflagellates based on ultrastructure and par-

tial LSU rDNA sequence data, including the erection of three new genera of unarmoured dinoflagellates.

Phycologia 39:302–17.

Destombe, C., and Cembella, A. (1990). Mating-type determination, gamete recognition and reproductive success in Alexandrium excavatum (Gonyaulacales, Dinophyta), a toxic red-tide dinoflagellate. Phycologia 29:315–25.

Dodge, J. D. (1971). Fine structure of the Pyrrophyta. Bot. Rev. 37:481–508.

Dodge, J. D., and Crawford, R. M. (1968). Fine structure of the dinoflagellate Amphidinium carteri Hulbert.

Protistologica 4:231–42.

Dodge, J. D., and Crawford, R. M. (1969). Observations of the fine structure of the eyespot and associated structures in the dinoflagellate Glenodinium foliaceum. J. Cell Sci. 5:479–93.

Dodge, J. D., and Crawford, R. M. (1970). A survey of thecal fine structure in the Dinophyceae. J. Linn. Soc. Bot. 63:53–67.

Downie, C. (1956). Microplankton from the Kimmeridge Clay. Q. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 112:413–34.

Dunlap, J. C., and Hastings, J. W. (1981). Biochemistry of dinoflagellate bioluminescence: Purification and characterization of dinoflagellate luciferin from Pyrocystis lunula. Biochemistry

20:983–9.

Ellegaard, M., Christensen, N. F., and Moestrup, O. (1994). Dinoflagellate cysts from recent Danish marine sediments. Eur. J. Phycol. 29:183–94.

Eppley, R. W., Holm-Hansen, O., and Strickland, J. D. H. (1968). Some observations on the vertical migration of dinoflagellates. J. Phycol. 4:333–40.

Faust, M. A. (1990). Morphological details of six benthic species of Prorocentrum (Pyrrophyta) from a mangrove island, Twin Cays, Belize, including two new species. J. Phycol. 26:548–58.

Faust, M. A. (1995). Observation of sand-dwelling toxic dinoflagellates (Dinophyceae) from widely differing sites, including two new species. J. Phycol.

31:996–1003.

Fenchel, T. (2001). How dinoflagellates swim. Protist 152:329–38.

Fritz, L., Milos, P., Morse, D., and Hastings, J. W. (1991). In situ hybridization of luciferase-binding protein anti-sense RNA to thin sections of the bioluminescent dinoflagellate Gonyaulax polyedra. J. Phycol. 27:436–41.

Gaines, G., and Taylor, F. J. R. (1984). Extracellular digestion in marine dinoflagellates. J. Plank. Res. 6:1057–61.

DINOPHYTA 305

Gaines, G., and Taylor, F. J. R. (1985). Form and function of the dinoflagellate transverse flagellum. J. Protozool. 32:290–6.

Gallois, R. W. (1976). Coccolith blooms in the Kimmeridge Clay and origin of the North Sea oil. Nature 259:473–5.

Garbary, D. J., and Wynne, M. J. (1996). Prominent Phycologists of the 20th Century. Hantsport, Nova Scotia: Lancelot Press.

Gattuso, J.-P., Reynaud-Vaganay, S., Furla, P., RomaineLioud, S., and Jaubert, J. (2000). Calcification does not stimulate photosynthesis in the zooxanthellate scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata. Limnol. Oceanogr. 45:246–50.

Gao, X-P., and Li, J-Y. (1986). Nuclear division in the marine dinoflagellate Oxyrrhis marina. J. Cell Sci . 85:161–75.

Giner, J.-L., Faraldos, J. A., and Boyer, G. L. (2003). Novel sterols of the toxic dinoflagellate Karenia brevis (Dinophyceae): a defensive function for unusual marine sterols. J. Phycol. 39:315–19.

Graham, H. W., and Bronikovsky, N. (1944). The genus Ceratium in the Pacific and North Atlantic oceans.

Carnegie Inst. Washington Publ. 565:1–209. Green, B. R. (2004). The chloroplast genome of

dinoflagellates: a reduced instruction set? Protist 155:23–31.

Grindley, J. R., and Nel, E. A. (1970). Red water and mussel poisoning at Elands Bay, December 1966. Fish Bull., S. Afr. 6:36–55.

Grindley, J. R., and Sapeika, N. (1969). The cause of mussel poisoning in South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 43:275–9.

Gruet, C. (1965). Structure fine de l’ocelle d’Erythropsis pavillardi Hetwig, Péridinien

Warnowiidae Lindemann. C. R. Séances Acad. Sci., Paris

261:1904–7.

Guisande, C., Frangopulos, M., Carolenuto, Y., Maneiro, I., Riveiro, I., and Vergara, A.R. (2002). Fate of paralytic shellfish poisoning toxins ingested by the copepod Acartia clausi. Mar. Ecol. Progr. Ser. 240:105–15.

Hackett, J. D., Anderson, D. M., Erdner, D. L., and Bhattacharya, D. (2004). Dinoflagellates: a remarkable evolutionary experiment. Amer. J. Bot. 91:1523–34.

Hallegraeff, G. M. (1993). A review of harmful algal blooms and their apparent global increase.

Phycologia 32:79–99.

Hansen, G. (1989). Ultrastructure and morphogenesis of scales in Katodinium rotundatum (Lohmann) Loeblich (Dinophyceae). Phycologia 28:385–94.

Hansen, G. (1993). Light and electron microscopical observation of the dinoflagellate Actiniscus pentasterias (Dinophyceae). J. Phycol. 29:486–99.

Hansen, P. J., and Calado, A. J. (1999). Phagotrophic mechanisms and prey selection in free-living dinoflagellates. J. Eukary. Microbiol. 46:382–9.

Hansen, P. J., Miranda, L., and Azanza, R. (2004). Green Noctiluca scintillans: a dinoflagellate with its own greenhouse. Mar. Ecol. Progr. Ser. 275:79–87.

Happach-Kasan, C. (1982). Beobachtungen zum Bau der Theka von Ceratium cornutum, (Ehrenb,)

Clap. et Lachm. (Dinophyta). Arch. Protistenk. 125:181–207.

Harvey, E. N. (1952). Bioluminescence. New York: Academic Press.

Hastings, J. W. (1983). Biological diversity, chemical mechanisms, and the evolutionary origins of bioluminescent systems. J. Mol. Evol. 19:309–21.

Hastings, J. W. (1986). Bioluminescence in bacteria and dinoflagellates. In Light Emission in Plants and Bacteria, pp. 363–98. New York: Academic Press.

Hastings, J. W., and Krasnow, R. (1981). Temporal regulation in the individual Gonyaulax cell. In

International Cell Biology 1980–1981, Proc. 2nd Int. Cong. on Cell Biology, pp. 815–823. Berlin: SpringerVerlag.

Haywood, A. J., Steidinger, K. A., Truby, E. W., et al. (2004). Comparative morphology and molecular phylogenetic analysis of three new species of the genus Karenia (Dinophyceae) from New Zealand. J. Phycol. 40:165–79.

Höhfeld, I., and Melkonian, M. (1992). Amphiesmal ultrastructure of dinoflagellates, A reevaluation of pellicle formation. J. Phycol. 28:82–9.

Höhfeld, I., and Melkonian, M. (1998). Lifting the curtain? The microtubular cytoskeleton of Oxyrrhis marina (Dinophyceae) and its rearrangement during phagocytosis. Protist 149:75–88.

Höhfeld, I., Otten, J., and Melkonian, M. (1988). Contractile eukaryotic flagella: Centrin is involved.

Protoplasma 147:16–24.

Horiguchi, T., and Pienaar, R. N. (1988). Ultrastructure of a new sand-dwelling dinoflagellate Scrippsiella arenicola sp. nov. J. Phycol. 24:426–38.

Horiguchi, T., Kawai, H., Kubota, M., Takahasdi, T., and Watanabe, M. (1999). Phototactic responses of four marine dinoflagellates with different types of eyespot and chloroplast. Phycol. Res. 47:101–7.

Hu, T., Burton, I., Curtis, J. M., et al. (1999). Oxidative transformation of a naturally occurring okadaic acid diol ester by the diatom Thalassiosira weisflogii. Tetrahedron Lett. 40:3981–4.

306 CHLOROPLAST E.R.: EVOLUTION OF ONE MEMBRANE

Igarashi, T., Aritake, S., and Yasumoto, T. (1999). Mechanisms underlying the hemolytic and ichthyotoxic activities of maitotoxin. Nat. Toxins 7:71–9.

Ishida, K., and Green, B. R. (2002). Secondand thirdhand chloroplasts in dinoflagellates: phylogeny of oxygen-evolving enhancer 1 (PsbO) protein reveals replacement of a nuclear-encoded plastid gene by that of a haptophye tertiary endosymbiosis. Proc.

Natl. Acad. Sci., USA 99:9294–9.

Iwataki, M., Hansen, G., Sawaguchii, T., Hiroishi, S., and Fukuyo, Y. (2004). Investigations of body scales in twelve Heterocapsa species (Peridiniales, Dinophyceae), including a new species H. pseudotriquetra sp. nov. Phycologia 43:394–403.

Jacobsen, D. M. (1999). A brief history of dinoflagellate feeding research. J. Eukary. Microbiol. 46:376–81.

Jacobsen, D. M., and Anderson, D. M. (1986). Thecate heterotrophic dinoflagellates: Feeding behavior and mechanisms. J. Phycol. 22:249–58.

Janofske, B. (2000). Scrippsiela trochoidea and Scrippsiela regalis, nov. comb. (Peridiniales, Dinophyceae): a comparison. J. Phycol. 36:178–89.

John, E. H., and Flynn, K. J. (2002). Modelling changes in paralytic shellfish toxin content of dinoflagellates in response to nitrogen and phosphorus supply.

Mar. Ecol. Progr. Ser. 225:147–60.

Johnson, C. H., and Hastings, J. W. (1986). The elusive mechanism of the circadian clock. Am. Sci. 74:29–36.

Johnson, C. H., Inoué, S., Flint, A., and Hastings, J. W. (1985). Compartmentalization of algal bioluminescence: Autofluoresence of bioluminescent particles in the dinoflagellate Gonyaulax as studied with image-intensified video microscopy and flow cytometry. J. Cell Biol. 100:1435–46.

Juhl, A. R., and Latz, M. J. (2002). Mechanisms of fluid shear-induced inhibition of population growth in a red-tide dinoflagellate. J. Phycol. 38:683–94.

Keeling, P. J. (2004). Diversity and evolutionary history of plastids and their hosts. Amer. J. Bot. 91:1481–93.

Kennaway, G. M., and Lewis, J. M. (2004). An ultrastructural study of hypnospores of Alexandrium species (Dinophyceae). Phycologia 43:353–63.

Klut, M. E., Bisalputra, T., and Antia, N. J. (1985). Some cytochemical studies on the cell surface of

Amphidinium carteri (Dinophyceae). Protoplasma

129:93–9.

Kokinos, J. P., Eglinton, T. I., Goni, M., Boon, J. J., Martoglio, P. A., and Anderson, D. A. (1998). Characterization of a highly resistant biomacromolecular material in the cell wall of a marine dinoflagellate resting cyst. Org. Geochem. 28:265–88.

Kremp, A. (2001). Effects of cyst resuspension on germination and seeding of two bloom-forming dinoflagellates in the Baltic Sea. Mar. Ecol. Progr. Ser. 216:57–66.

Kubai, D. F., and Ris, H. (1969). Division in the dinoflagellate Gyrodinium cohnii (Schiller). A new type of nuclear reproduction. J. Cell Biol. 40:508–28.

Leadbeater, B. S. C., and Dodge, J. D. (1967a). Fine structure of the dinoflagellate transverse flagellum. Nature 213:421–2.

Leadbeater. B. S. C., and Dodge, J. D. (1967b). An electron microscope study of nuclear and cell division in a dinoflagellate. Arch. Mikrobiol. 57:239–54.

Leblond, J. D., and Chapman, P. J. (2002). A survey of the sterol composition of the marine dinoflagellates

Karenia brevis, Karenia mikimoto, and Karlodinium micrum: distribution of sterols within other members of the class Dinophyceae. J. Phycol. 38:670–82.

Lee, R. E. (1977). Saprophytic and phagocytic isolates of the colorless heterotrophic dinoflagellate

Gyrodinium lebouriae Herdman J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK

57:303–15.

Lewitus, A. J., Glasgow, H. B., and Burkholder, J. M. (1999). Kleptoplastidy in the toxic dinoflagellate

Pfiesteia piscicida (Dinophyceae). J. Phycol. 35:305–12. Loeblich, A. R. (1968). A new marine dinoflagellate

genus, Cachonia, in axenic culture from the Salton Sea, California with remarks on the genus

Peridinium. Proc. Biol. Soc. Wash. 81:91–6.

Loeblich, A. R. (1974). Protistan phylogeny as indicated by the fossil record. Taxon 23:277–90.

Loeblich, A. R. (1976). Dinoflagellate evolution: Speculation and evidence. J. Protozol. 23:13–28.

Lombard, E. H., and Capon, B. (1971). Observations on the tide pool behaviour of Peridinium gregarium. J. Phycol. 7:188–94.

MacRae, R. A., Fensome, R. A., and Williams, G. L. (1996). Fossil dinoflagellate diversity, originations, and extinctions and their significance. Can. J. Bot. 74:1687–94.

Maruyama, T. (1982). Fine structure of the longitudinal flagellum in Ceratium tripos, a marine dinoflagellate. J. Cell Sci. 58:109–23.

Maruyama, T. (1985). Ionic control of the longitudinal flagellum in Ceratium tripos (Dinoflagellida). J. Protozool. 3:106–10.

Matsuoka, K., Cho, H.-J., and Jacobsen, D. M. (2000). Observations of the feeding behavior and growth rates of the heterotrophic dinoflagellate Polykrikos kofoidii (Polykrikaceae, Dinophyceae). Phycologia 39:82–6.

DINOPHYTA 307

Meksumpun, S., Montani, S., and Uematsu, M. (1994). Elemental composition of cell walls of three marine phytoflagellates, Chattonella antiqua

(Raphidophyceae), Alexandrium catenella and

Scrippsiella trochoidea (Dinophyceae). Phycologia

33:275–80.

Messer, G., and Ben-Shaul, Y. (1969). Fine structure of Peridinium westii Lemm., a freshwater dinoflagellate. J. Protozool. 16:272–80.

Montresor, M., Janofske, D., and Willems, H. (1997). The cyst-theca relationship in Calciodinellum operosum emend. (Peridinales, Dinophyceae) and a new approach for the study of calcareous cysts. J. Phycol. 33:122–31.

Moronin, L., and Francis, D. (1967). The fine structure of Nematodinium armatum, a naked dinoflagellate. J. Microscopie 6:759–72.

Morrill, L. C., and Loeblich, A. R. (1983a). Ultrastructure of the dinoflagellate amphisema. Int. Rev. Cytol. 82:151–80.

Morrill, L. C., and Loeblich, A. R. (1983b). Formation and release of body scales in the dinoflagellate genus Heterocapsa. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 63:905–13.

Morton, S. L., and Tindall, D. R. (1995). Morphological and biochemical variability of the toxic dinoflagellate Prorocentrum lima isolated from three locations at Heron Island, Australia. J. Phycol. 31:914–21.

Nagai, S., Matsuyama, Y., Takayama, H., and Kotani, Y. (2002). Morphology of Polykrikos kofoidii and P. schwartzii (Dinophyceae, Polykrikaceae) cysts obtained in culture. Phycologia 41:319–27.

Nagai, S., Itakura, S., Matsuyama, Y., and Kotani, Y. (2003). Encystment under laboratory conditions of the toxic dinoflagellate Alexandrium tamiyavanichii

(Dinophyceae) isolated from Seto Island Sea, Japan.

Phycologia 42:646–53.

Naustvoll, L.-J. (1998). Growth and grazing by the thecate heterotrophic dinoflagellate Diplopsalis lenticula (Diplopsalidaceae, Dinophyceae). Phycologia 37:1–9.

Nawata, T., and Sibaoka, T. (1983). Experimental induction of feeding behavior in Noctiluca miliaris. Protoplasma 115:34–42.

Nawata, T., and Sibaoka, T. (1987). Local ion currents controlling the localized cytoplasmic movement associated with feeding initiation of Noctiluca. Protoplasma 137:125–33.

Nicolas, M. T., Morse, D., Bassot, J-M. and Hastings, J. W. (1991). Colocalization of luciferin binding protein and luciferase to the scintillons of Gonyaulax polyedra revealed by double immunolabeling after fast-freeze fixation. Protoplasma 160:159–66.

Perez, C. C., Roy, S., Levasseur, M., and Andersen, D. M. (1998). Control of germination of Alexandrium tamarensis (Dinophyceae) cysts from the lower St. Lawrence estuary (Canada). J. Phycol. 34:242–9.

Pöggeler, B., Balzer, I., Hardeland, R., and Lerchl, A. (1991). Pineal hormone melatonin oscillates also in the dinoflagellate Gonyaulax polyedra. Naturwissenschaften 78:268–9.

Preisig, H. R. (1994). Siliceous structures and silicification in flagellated protists. Protoplasma 181:1–28.

Prézilin, B. B. (1976). The role of peridinin-chlorophyll a-proteins in the photosynthetic light adaptation of the marine dinoflagellate, Glenodinium sp. Planta 130:225–33.

Prézilin, B. B., and Haxo, F. T. (1976). Purification and characterization of peridinin-chlorophyll -proteins from the marine dinoflagellates Glenodinium sp. and

Gonyaulax polyedra. Planta 128:133–41.

Raven, J. A., and Richardson, K. (1984). Dinophyte flagella: A cost–benefit analysis. New Phytol. 98:259–76.

Ris, H., and Kubai, D. F. (1974). An unusual mitotic mechanism in the parasitic protozoan Syndinium sp. J. Cell Biol. 60:702–20.

Rizzo, P. J. (1991). The enigma of the dinoflagellate chromosome. J. Protozool. 38:246–52.

Roberts, K. R., and Roberts, J. E. (1991). The flagellar apparatus and cytoskeleton of the dinoflagellate.

Protoplasma 164:105–22.

Robinson, N., Eglinton, G., Brassell, S. C., and Cranwell, P. A. (1984). Dinoflagellate origin for sedimentary 4 -methylsteroids and 5 (H)-stanols. Nature 308:439–42.

Rodriguez-Lanetty, M., Krupp, D. A., and Weis, V. M. (2004). Distinct ITS types of Symbiodinium in Clade C correlate with cnidarian/dinoflagellate specificity during onset of symbiosis. Mar. Ecol. Progr. Ser. 275:97–102.

Roenneberg, T., and Deng, T-S. (1997). Photobiology of the Gonyaulax circadian system. I. Different phase response curves for red and blue light. Planta 202:494–501.

Sakamoto, B., Hokama, Y., Horgen, F. D., Scheuer, P. J., Kan, Y., and Nagai, H. (2000). Isolation of a sulfoquinovosyl monoacylglycerol from Bryopsis sp. (Chlorophyta): identification of a factor causing a possible species specific ecdysis response in

Gamierdiscus toxicus (Dinophyceae). J. Phycol. 36:924–31.

Samuelsson, G., Sweeney, B. M., Matlock, H. A., and Prézilin, B. B. (1983). Changes in photosystem II account for the circadian rhythm in photosynthesis in Gonyaulax polyedra. Plant Physiol. 73:329–31.

308 CHLOROPLAST E.R.: EVOLUTION OF ONE MEMBRANE

Schiller, J. (1933). Dinoflagellatae. In Dr L. Rabenhorst’s Kryptogamen-Flora, Vol. 10. pp. 1–617. Leutershausen: Strauss and Cramer.

Schmidt, R. J., Gooch, V. D., Loeblich, A. R., and Hastings, J. W. (1978). Comparative study of luminescent and nonluminescent strains of

Gonyaulax excavata (Pyrrhophyta). J. Phycol. 14:5–9. Schütt, F. (1895). Die Peridineen der Plankton-

Expedition. Ergeb. Plankton Exped. Humboldt-Stiftung. 4; M.a. A:1–170.

Sekida, S., Horiguchi, T., and Okuda, K. (2004). Development of thecal plates and pellicle in the dinoflagellate Scrippsiella hexapraecingula

(Peridiniales, Dinophyceae) elucidated by changes in stainability of the associated membranes. Eur. J. Phycol. 39:105–14.

Seo, K. S., and Fritz, L. (2000). Cell ultrastructural changes correlate with circadian rhythms in

Pyrocystis lunula (Pyrrophyta). J. Phycol. 36:351–8. Sgrosso, S., Esposito, F., and Montresor, M. (2001).

Temperature and daylength regulate encystment in calcareous cyst-forming dinoflagellates. Mar. Ecol. Progr. Ser. 211:77–87.

Shilo, M. (1967). Information and mode of action of algal toxins. Bacteriol. Rev. 31:180–93.

Sigee, D. C. (1984). Structural DNA and genetically active DNA in dinoflagellate chromosomes.

BioSystems 16:302–10.

Smalley, G. W., Coats, D. W., and Stoecker, D. K. (2003). Feeding in the mixotrophic dinoflagellate Ceratium furca is influenced by intracellular nutrient concentrations. Mar. Biol. Progr. Ser. 262:137–51.

Spero, H. J. (1982). Phagotrophy in Gymnodinium fungiforme (Pyrrophyta): The peduncle as an organelle of ingestion. J. Phycol. 18:356–60.

Spero, H. J. (1985). Chemosensory capabilities in the phagotrophic dinoflagellate Gymnodinium fungiforme. J. Phycol. 21:181–4.

Spero, H. J., and Moree, M. D. (1981). Phagotrophic feeding and its importance to the life cycle of the holozoic dinoflagellate, Gymnodinium fungiforme. J. Phycol. 17:43–57.

Sullivan, J. M., and Swift, E. (2003). Effects of smallscale turbulence on net growth rate and size of ten species of marine dinoflagellates. J. Phycol. 39:83–94.

Sulzman, F. N., Krieger, N. R., Gooch, V. D., and Hastings, J. W. (1978). A circadian rhythm of the luciferin binding protein from Gonyaulax polyedra. J. Comp. Physiol. 128:251–7.

Suzuki, L., and Johnson, C. H. (2001). Algae know the time of day: circadian and photoperiodic programs. J. Phycol. 37:933–42.

Suzuki, T., Mitsuya, T., Imai, M., and Yamasaki, M. (1997). DSP toxin contents in Dinophysis fortii and scallops collected at Mutsu Bay, Japan. J. Applied Phycol. 8:509–15.

Sweeney, B. M. (1969). Rhythmic Phenomena in Plants. London and New York: Academic Press.

Sweeney, B. M. (1971). Laboratory studies of a green Noctiluca from New Guinea. J. Phycol. 7:53–8.

Sweeney, B. M. (1978). Ultrastructure of Noctiluca miliaris (Pyrrophyta) with green flagellate symbionts. J. Phycol. 14:116–20.

Sweeney, B. M. (1979). The bioluminescence of dinoflagellates. In Biochemistry and Physiology of Protozoa, ed. M. Levandowsky, and S. H. Hutner, Vol. 1,

pp. 287–306. New York: Academic Press.

Sweeney, B. M. (1980). Intracellular source of bioluminescence. Int. Rev. Cytol. 68:173–95.

Swift, E., Biggley, W. H., and Seliger, H. H. (1973). Species of oceanic dinoflagellates in the genera

Dissodinium and Pyrocystis: Interclonal and intraspecific comparisons of color and photon yield of bioluminescence. J. Phycol. 9:420–6.

Takishita, K., Ishida, K.-I., Ishikura, M., and Maruyama. T. (2005). Phylogeny of the psbC gene, coding a photosystem II component CP 43, suggests separate origins for the peridininand fucoxanthin derivative-containing plastids of dinoflagellates.

Phycologia 44:26–34.

Taylor, D. L. (1969). On the regulation and maintenance of algal numbers in zooxanthellae-coelenterate symbiosis, with a note on the nutritional relationship in Anemonia sulcata. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK

49:1057–65.

Taylor, D. L. (1971). On the symbiosis between

Amphidinium klebsii (Dinophyceae) and Amphiscolops langerhansi (Turbellaria: Acoela). J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK

51:301–13.

Taylor, F. J. R. (1971). Scanning electron microscopy of thecae of the dinoflagellate genus Ornithocercus. J. Phycol. 7:249–58.

Taylor, F. J. R. (1999). Morphology (tabulation) and molecular evidence for dinoflagellate phylogeny reinforce each other. J. Phycol. 35:1–3.

Trench, R. K. (1993). Microlgal–invertebrate symbioses: a review. Endocytobios Cell Res. 9:135–75.

Triemer, R. E. (1982). A unique mitotic variation in the marine dinoflagellate Oxyrrhis marina (Pyrrophyta). J. Phycol. 18:399–411.

Vogel, K., and Meeuse, B. J. D. (1968). Characterization of the reserve granules from the

dinoflagellate Thecadinium inclination Balech. J. Phycol. 4:317–18.

DINOPHYTA 309

von Stosch, H. A. (1972). La signification cytologique de la “cyclose nucléaire” dans le cycle de vie des Dinoflagellés. Soc. Bot. Fr., Memoires, pp. 201–12.

von Stosch, H. A. (1973). Observations on vegetative reproduction and sexual life cycles of two freshwater dinoflagellates, Gymnodinium pseudopalustre Schiller and Woloszynskia apiculata sp. nov. Br. Phycol. J. 8:105–34.

Wang, J-T., and Douglas, A. E. (1997). Nutrients signals and photosynthate release by symbiotic algae. Plant Physiol. 114:631–6.

Wilcox, L. W., and Wedemeyer, G. J. (1991). Phagotrophy in the freshwater photosynthetic dinoflagellate Amphidinium cryophilum. J. Phycol. 27:600–9.

Windust, A. J., Hu, T., Wright, J. L. C., Quilliam, M. A., and McLachlan, J. L. (2000). Oxidative metabolism by

Thalassiosira weisflogii (Bacillariophyceae) of a

diol-ester of okadaic acid, the diarrhetic shellfish poisoning. J. Phycol. 36:342–50.

Withers, N. (1982). Ciguatera fish poisoning. Annu. Rev. Med. 33:97–111.

Yoon, H. S., Hackett, J. D., and Bhattacharya, D. (2002). A single origin of the peridininand fucoxanthincontaining plastids in dinoflagellates through tertiary endosymbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., USA

99:11724–9.

Zardoya, R., Costas, E., Lopez-Rodas, V., GarridoPertierra, A., and Bautista, J. M. (1995). Revised dinoflagellate phylogeny inferred from molecular analysis of large-subunit ribosomal RNA sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 41:637–45.

Zhou, J., and Fritz, L. (1994). Okadaic acid localizes to chloroplasts in the DSP-toxin-producing dinoflagellates Prorocentrum lima and Prorocentrum maculosum. Phycologia 33:455–61.

Chapter 8

Apicomplexa

Algae are organisms that have plastids, or organisms that are derived from cells whose ancestors possessed plastids. Until 1994, it was thought that the apicomplexa did not have plastids (and consequently were not covered in phycology textbooks). Then it was shown that a known organelle in many apicomplexa was actually a reduced

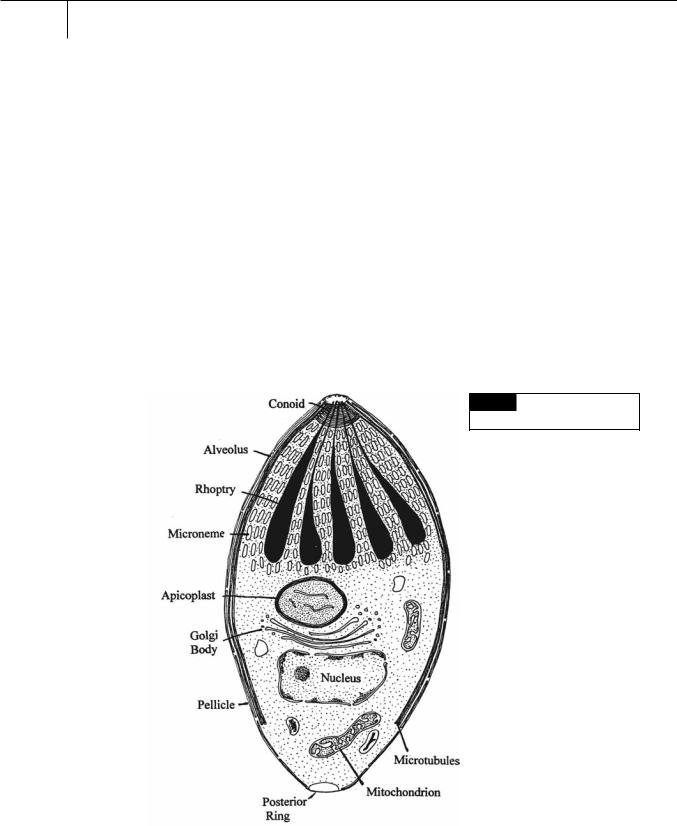

colorless plastid called an apicoplast (Fig. 8.1) (Wilson, 1993; Wilson et al., 1994). Molecular studies have shown that the apicoplast and dinoflagellate plastids originated from red algae by a single endosymbiotic event that occurred relatively early in eukaryotic evolution (Fast et al., 2001).

Fig. 8.1 Drawing of the basic

cytology of an apicomplexan cell.

APICOMPLEXA 311

Fig. 8.2 General scheme by which an apicomplexan infects a blood cell. The apicomplexan has a characteristic laminin polysaccharide on the surface of the plasma membrane that binds with laminin receptors on the blood cell. This forms a tight junction between the apicomplexan and blood cell. The apicomplexan discharges its rhoptries. The blood cell phagocytoses the apicomplex into a parasitophorous vacuole. (Modified from Sam-Yellowe, 1996.)

The discovery of the apicoplast generated considerable interest since most apicomplexans are unicellular endoparasites that cause some of the most significant tropical diseases (Foth and McFadden, 2003). Malaria in humans is produced by the apicomplexan Plasmodium. About 300 million people are infected with malaria, leading to one million deaths annually (Ralph et al., 2004). Apicomplexans cause other serious diseases in livestock and humans, such as cryptosporidiosis, babesiosis (Texas cattle fever), theileriosis (East Coast fever), and toxoplasmosis. The realization that these endoparasites were once algae raised hopes that the apicoplast might be a drug target for two reasons. The first is that the apicoplast is essential for the survival of Plasmodium and

Toxoplasma. The second is that drugs effective against prokaryotic organisms might be effective against the apicoplast since all plastids originally evolved from endosymbiotic prokaryotic cyanobacteria. Apicomplexans are absolutely dependent on the apicoplast, which has led to speculation that this curious organelle is a potential “Achilles heel” of parasites, such as Plasmodium.

The typical apicomplexan vegetative cell (merozoite) (Fig. 8.1) has an apicoplast surrounded by four membranes. The inner two membranes are the inner and outer plastid membranes while the outer membranes are derived from the vacuolar membrane and the plasma membrane of the endosymbiotic red alga.

The apical complex consists of a polar ring and a conoid formed of spirally coiled microtubules (Fig. 8.1). The apicomplexan has laminin polysaccharide on its surface while the host cell has a laminin receptor (Fig. 8.2). The apicomplexan parasite attaches to the host cell with the conoid protruding to produce a stylet that forms a tight junction between the apicomplexan parasite and host cell. The apicomplexan cell is taken

312 CHLOROPLAST E.R.: EVOLUTION OF ONE MEMBRANE

up into the host cell in the parasitophorous vacuole. The contents of the rhoptries and micronemes are emptied into the space between the apicomplexan plasma membrane and the parasitophorous vacuole membrane.

Apicomplexans have a layer of flattened membranous sacs or alveoli (Fig. 8.1) beneath the plasma membrane that comprise the subpellicular membrane complex, similar to that found in the dinoflagellates.

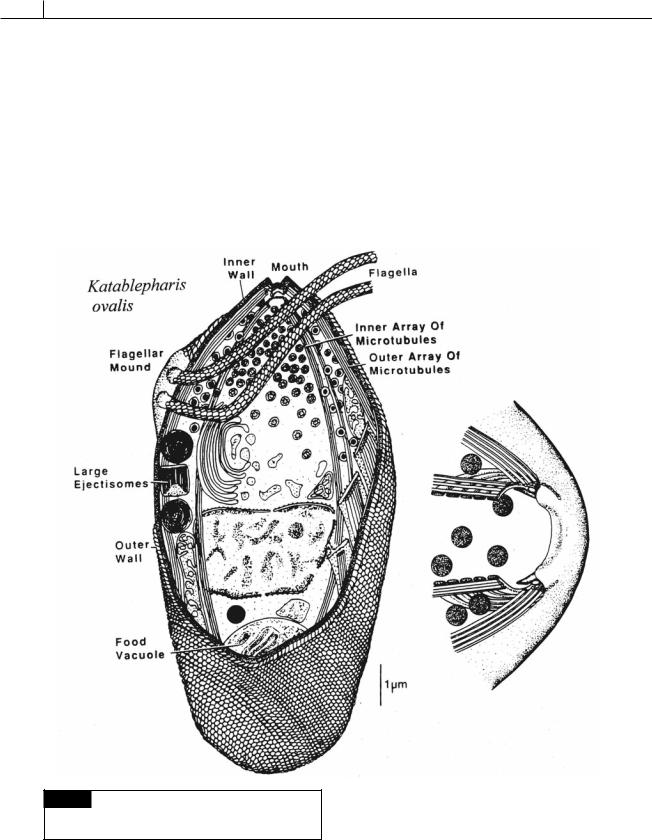

Katablepharis (Fig. 8.3) is a heterotrophic unicellular flagellate that lacks a plastid. Katablepharis cells have ejectisomes and was classified with the Cryptophyceae. However, ultrastructural studies (Lee and Kugrens, 1991; Lee et al., 1991) revealed the presence of an anterior conoid apparatus involved in phagocytosis of prey. The conoid apparatus is very similar to those of the apicomplexans and it is likely that Katablepharis should be classified as an apicomplexan.

Fig. 8.3 Drawings of Katablepharis ovalis. Left: whole cell.

Right: anterior part of cell. (From Lee and Kugrens, 1991; Lee

et al., 1991.)