- •Contents

- •Preface to the first edition

- •Flagella

- •Cell walls and mucilages

- •Plastids

- •Mitochondria and peroxisomes

- •Division of chloroplasts and mitochondria

- •Storage products

- •Contractile vacuoles

- •Nutrition

- •Gene sequencing and algal systematics

- •Classification

- •Algae and the fossil record

- •REFERENCES

- •CYANOPHYCEAE

- •Morphology

- •Cell wall and gliding

- •Pili and twitching

- •Sheaths

- •Protoplasmic structure

- •Gas vacuoles

- •Pigments and photosynthesis

- •Akinetes

- •Heterocysts

- •Nitrogen fixation

- •Asexual reproduction

- •Growth and metabolism

- •Lack of feedback control of enzyme biosynthesis

- •Symbiosis

- •Extracellular associations

- •Ecology of cyanobacteria

- •Freshwater environment

- •Terrestrial environment

- •Adaption to silting and salinity

- •Cyanotoxins

- •Cyanobacteria and the quality of drinking water

- •Utilization of cyanobacteria as food

- •Cyanophages

- •Secretion of antibiotics and siderophores

- •Calcium carbonate deposition and fossil record

- •Chroococcales

- •Classification

- •Oscillatoriales

- •Nostocales

- •REFERENCES

- •REFERENCES

- •REFERENCES

- •RHODOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Cell walls

- •Chloroplasts and storage products

- •Pit connections

- •Calcification

- •Secretory cells

- •Iridescence

- •Epiphytes and parasites

- •Defense mechanisms of the red algae

- •Commercial utilization of red algal mucilages

- •Reproductive structures

- •Carpogonium

- •Spermatium

- •Fertilization

- •Meiosporangia and meiospores

- •Asexual spores

- •Spore motility

- •Classification

- •Cyanidiales

- •Porphyridiales

- •Bangiales

- •Acrochaetiales

- •Batrachospermales

- •Nemaliales

- •Corallinales

- •Gelidiales

- •Gracilariales

- •Ceramiales

- •REFERENCES

- •Cell structure

- •Phototaxis and eyespots

- •Asexual reproduction

- •Sexual reproduction

- •Classification

- •Position of flagella in cells

- •Flagellar roots

- •Multilayered structure

- •Occurrence of scales or a wall on the motile cells

- •Cell division

- •Superoxide dismutase

- •Prasinophyceae

- •Charophyceae

- •Classification

- •Klebsormidiales

- •Zygnematales

- •Coleochaetales

- •Charales

- •Ulvophyceae

- •Classification

- •Ulotrichales

- •Ulvales

- •Cladophorales

- •Dasycladales

- •Caulerpales

- •Siphonocladales

- •Chlorophyceae

- •Classification

- •Volvocales

- •Tetrasporales

- •Prasiolales

- •Chlorellales

- •Trebouxiales

- •Sphaeropleales

- •Chlorosarcinales

- •Chaetophorales

- •Oedogoniales

- •REFERENCES

- •REFERENCES

- •EUGLENOPHYCEAE

- •Nucleus and nuclear division

- •Eyespot, paraflagellar swelling, and phototaxis

- •Muciferous bodies and extracellular structures

- •Chloroplasts and storage products

- •Nutrition

- •Classification

- •Heteronematales

- •Eutreptiales

- •Euglenales

- •REFERENCES

- •DINOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Theca

- •Scales

- •Flagella

- •Pusule

- •Chloroplasts and pigments

- •Phototaxis and eyespots

- •Nucleus

- •Projectiles

- •Accumulation body

- •Resting spores or cysts or hypnospores and fossil Dinophyceae

- •Toxins

- •Dinoflagellates and oil and coal deposits

- •Bioluminescence

- •Rhythms

- •Heterotrophic dinoflagellates

- •Direct engulfment of prey

- •Peduncle feeding

- •Symbiotic dinoflagellates

- •Classification

- •Prorocentrales

- •Dinophysiales

- •Peridiniales

- •Gymnodiniales

- •REFERENCES

- •REFERENCES

- •Chlorarachniophyta

- •REFERENCES

- •CRYPTOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Ecology

- •Symbiotic associations

- •Classification

- •Goniomonadales

- •Cryptomonadales

- •Chroomonadales

- •REFERENCES

- •CHRYSOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Flagella and eyespot

- •Internal organelles

- •Extracellular deposits

- •Statospores

- •Nutrition

- •Ecology

- •Classification

- •Chromulinales

- •Parmales

- •Chrysomeridales

- •REFERENCES

- •SYNUROPHYCEAE

- •Classification

- •REFERENCES

- •EUSTIGMATOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCES

- •PINGUIOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCES

- •DICTYOCHOPHYCEAE

- •Classification

- •Rhizochromulinales

- •Pedinellales

- •Dictyocales

- •REFERENCES

- •PELAGOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCES

- •BOLIDOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCE

- •BACILLARIOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Cell wall

- •Cell division and the formation of the new wall

- •Extracellular mucilage, biolfouling, and gliding

- •Motility

- •Plastids and storage products

- •Resting spores and resting cells

- •Auxospores

- •Rhythmic phenomena

- •Physiology

- •Chemical defense against predation

- •Ecology

- •Marine environment

- •Freshwater environment

- •Fossil diatoms

- •Classification

- •Biddulphiales

- •Bacillariales

- •REFERENCES

- •RAPHIDOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCES

- •XANTHOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Cell wall

- •Chloroplasts and food reserves

- •Asexual reproduction

- •Sexual reproduction

- •Mischococcales

- •Tribonematales

- •Botrydiales

- •Vaucheriales

- •REFERENCES

- •PHAEOTHAMNIOPHYCEAE

- •REFERENCES

- •PHAEOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Cell walls

- •Flagella and eyespot

- •Chloroplasts and photosynthesis

- •Phlorotannins and physodes

- •Life history

- •Classification

- •Dictyotales

- •Sphacelariales

- •Cutleriales

- •Desmarestiales

- •Ectocarpales

- •Laminariales

- •Fucales

- •REFERENCES

- •PRYMNESIOPHYCEAE

- •Cell structure

- •Flagella

- •Haptonema

- •Chloroplasts

- •Other cytoplasmic structures

- •Scales and coccoliths

- •Toxins

- •Classification

- •Prymnesiales

- •Pavlovales

- •REFERENCES

- •Toxic algae

- •Toxic algae and the end-Permian extinction

- •Cooling of the Earth, cloud condensation nuclei, and DMSP

- •Chemical defense mechanisms of algae

- •The Antarctic and Southern Ocean

- •The grand experiment

- •Antarctic lakes as a model for life on the planet Mars or Jupiter’s moon Europa

- •Ultraviolet radiation, the ozone hole, and sunscreens produced by algae

- •Hydrogen fuel cells and hydrogen gas production by algae

- •REFERENCES

- •Glossary

- •Index

422 CHLOROPLAST E.R.: EVOLUTION OF TWO MEMBRANES

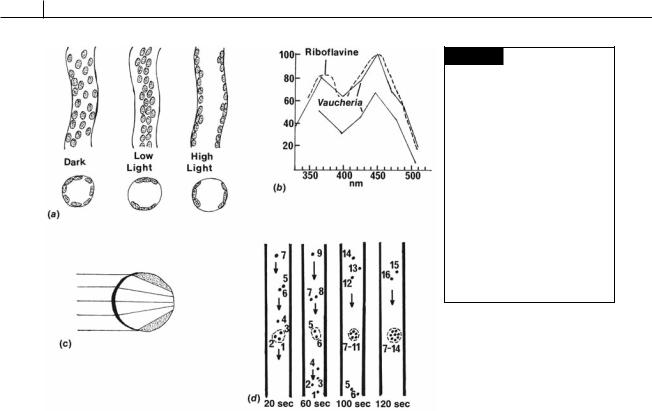

There are two possible mechanisms to explain chloroplast movement. In the first or “active movement” the chloroplast moves relative to the rest of the protoplasm, whereas in the second or “passive movement” the protoplasm moves, carrying with it the chloroplast and other organelles. In Vaucheria, passive movement occurs. If chloroplast movement is followed at high or low intensity, it can be seen that not only chloroplasts, but also other organelles and inclusions are rearranged by light. Furthermore, if only a small area of the filament is irradiated with a spot of light, a strong accumulation of cytoplasm plus inclusions can be observed at this place (Fig. 19.10(d)). The organelles are actually trapped in a portion of the cytoplasm as they stream through the cell. Illumination of an area of Vaucheria results in the formation of an actin fiber network that acts as a trapping mechanism (Blatt, 1983).

REFERENCES

Al-Kubaisi, K. H., and Schwantes, H. O. (1981). Cytophotometrische Untersichungen zum

Fig. 19.10 (a) Position of chloroplasts of Vaucheria in the dark, and in low and high light intensities. (b) Action spectrum of chloroplast orientation movement in Vaucheria under low light (lower curve) and high light (upper curve) intensities. Vertical axis is relative quantum efficiency. (c) Diagrammatic representation of the lens effect of light passing through a Vaucheria coenocyte. (d) Movements of single chloroplasts in Vaucheria under low light intensity. A beam of light (dashed area) causes accumulation of chloroplasts in the illuminated area. (After Haupt and Schönbohm, 1970.)

Generationswechel autotropher und heterotrophen siphonaler Organismen (Vaucheria sessilis und

Saprolegnia ferax). Nova Hedwigia 34:301–16.

Ariztia, E. V., Andersen, R. A., and Sogin, M. L. (1991). A new phylogeny for chromophyte algae using 16S-like rRNA sequences from Mallomonas papillosa

(Synurophyceae) and Tribonema aequales (Xanthophyceae). J. Phycol. 27:428–36.

Bailey, J. C., and Andersen, R. A. (1998). Phylogenetic relationships among nine species of the Xanthophyceae inferred from rbcL and 18S rRNA gene sequences. Phycologia 37:458–66.

Birckner, V. (1912). Die Beobachtung von Zoosporenbildung bei Vaucheria aversa Hass. Flora 104:167–71.

Blatt, M. R. (1983). The action spectrum for chloroplast movements and evidence for blue- light–photoreceptor cycling in the Vaucheria. Planta 159:267–76.

Cleare, M., and Percival, E. (1973). Carbohydrates of the freshwater alga Tribonema aequale. II. Preliminary photosynthetic studies with 14C. Br. Phycol. J. 8:181–4.

Deason, T. R. (1971). The fine structure of sporogenesis in the Xanthophycean alga Pseudobumilleriopsis pyrenoidosa. J. Phycol. 7:101–7.

HETEROKONTOPHYTA, XANTHOPHYCEAE |

423 |

|

|

Ehara, M., Hayashi-Ishimura, Y., Inagaki, Y., and Ohama, T. (1997). Use of a deviant mitochondrial genetic code in yellow-green algae as a landmark for segregating members within the phylum. J. Mol. Evol. 45:119–24.

Fischer-Arnold, G. (1963). Untersuchungen über die Chloroplastenbewegung bei Vaucheria sessilis. Protoplasma 56:495–506.

Greenwood, A. D. (1959). Observations on the structure of the zoospores of Vaucheria. II. J. Exp. Bot. 10:55–68.

Greenwood, A. D., Manton, I., and Clarke, B. (1957). Observations on the structure of the zoospores of

Vaucheria. J. Exp. Bot. 8:71–86.

Haupt, W., and Schönbohm, E. (1970). Light-oriented chloroplast movements. In Photobiology of Microorganisms; ed. P. Halldal, pp. 283–307. London: Wiley-Interscience.

Hibberd, D. J. (1981). Notes on the taxonomy and nomenclature of the algal classes Eustigmatophyceae and Tribophyceae (synonym Xanthophyceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 82:93–119.

Hibberd, D. J., and Leedale, G. F. (1971). Cytology and ultrastructure of the Xanthophyceae. II. The zoospore and vegetative cell of coccoid forms, with special reference to Ophiocytium majus Naegeli. Br. Phycol. J. 6:1–23.

Iyengar, M. O. P. (1925). Note on two species of

Botrydium from India. J. Indian Bot. Soc. 4:193–201. Klebs, G. (1896). Die Bedingungen de Fortpflanzung bei

einigen Algen und Pilzen. Jena.

Kolkwitz, R. (1926). Zur Ökologie und Systematic von

Botrydium granulatum (L) Grev. Ber. Dtsch. Bot. Ges.

44:533–40.

Lokhorst, G. M., and Star, W. (1988). Mitosis and cytokinesis in Tribonema regulare (Tribophyceae, Chrysophyta). Protoplasma 145:7–15.

Lokhorst, G. M., and Star, W. (2003). The flagellar apparatus in Tribonema (Xanthophyceae) reinvestigated.

Phycologia 42:31–43.

Marchant, H. J. (1972). Pyrenoids of Vaucheria woroniniana. Heering. Br. Phycol. J. 7:81–4.

Miller, V. (1927). Untersuchungen über die Gattung Botrydium Wallroth. II. Spezieller Teil. Ber Dtsch. Bot. Ges. 45:161–70.

Moestrup, Ø. (1970). On the fine structure of the spermatozoids of Vaucheria sescuplicaria and on later

stages in spermatogenesis. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 50:513–23.

Moore, G. T., and Carter, N. (1926). Further studies on the subterranean algal flora of the Missouri Botanical Garden. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 13:101–40.

Ott, D. W., and Brown, R. M., Jr. (1974a). Developmental cytology of the genus Vaucheria. I. Organization of the vegetative filament. Br. Phycol. J. 9:111–26.

Ott, D. W., and Brown, R. M., Jr. (1974b). Developmental cytology of the genus Vaucheria. II. Sporogenesis in V. fontinalis (L) Christensen. Br. Phycol. J. 9:333–51.

Ott, D. W., and Brown, R. M. (1978). Developmental cytology of the genus Vaucheria. IV. Spermatogenesis.

Br. Phycol. J. 13:69–85.

Parker, B. C., Preston, R. D., and Fogg, G. E. (1963). Studies of the structure and chemical composition of the cell walls of Vaucheriaceae and Saprolegniaceae. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. [B] 158:435–45.

Potter, D., Saunders, G. W., and Andersen, R. A. (1997). Phylogenetic relationships of the Raphidophyceae and Xanthophyceae as inferred from nucleotide sequences of the 18S ribosomal RNA gene. Am. J. Bot. 84:966–72.

Rakován, J. N., and Fridvalsky, L. (1970). Electron microscope studies on the gonidiogenesis of Botrydium granulatum (L) Grev. (Xanthophyceae). Ann. Univ. Sci. Budap. Sect. Biol. 12:209–12.

Rosenberg, M. (1930). Die geschlechtliche Fortpflanzung von Botrydium granulatum Grev. Oesterr. Bot. Z. 79:289–96.

Rostafin´ski, J., and Woronin, M. (1877). Ueber Botrydium granulatum. Bot. Zig. 35:649–71.

Scherffel, A. (1901). Kleiner Beitrag zur Phylogenie einiger Gruppen neiderer Organismen. Bot. Ztg. 59:143–58.

Smith, G. M. (1938). Cryptogamic Botany, Vol. 1. Algae and Fungi. New York and London: McGraw-Hill.

Smith, G. M. (1950). The Fresh-Water Algae of the United States, 2nd edn. New York and London: McGraw Hill.

Starr, R. C. (1964). The culture collection of algae at Indiana University. Am. J. Bot. 51:1013–44.

Sullivan, C. M., Entwisle, T. J., and Rowan, K. S. (1990). The identification of chlorophyll c in the Tribophyceae ( Xanthophyceae) using spectrophotofluorometry. Phycologia 29:285–91.

Chapter 20

Heterokontophyta

PHAEOTHAMNIOPHYCEAE

Recent nucleotide sequencing has uncovered an evolutionary line of golden-brown algae not related to other golden-brown algae (Bailey et al., 1998). These algae have been placed in the class Phaeothamniophyceae, a class that is most closely

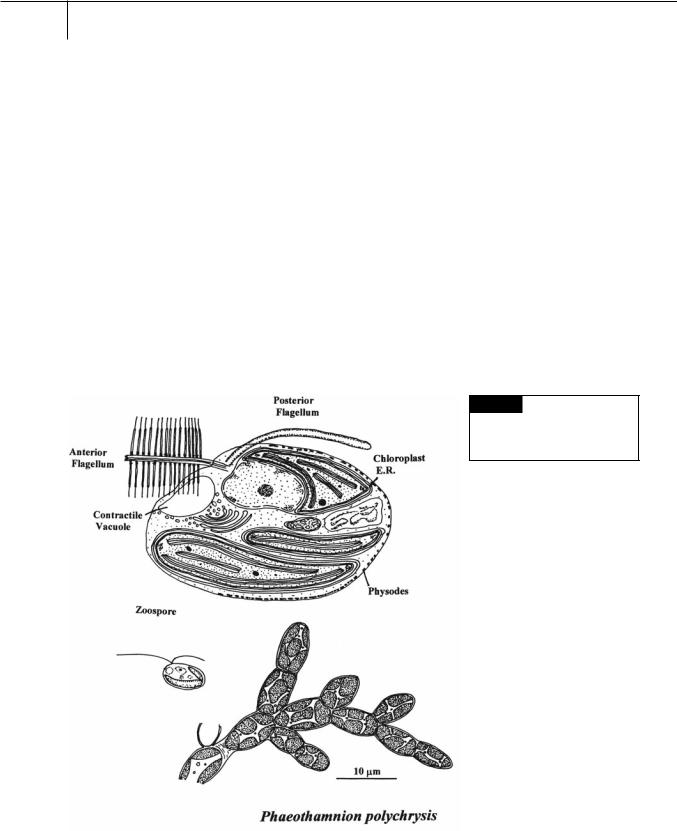

related to the Xanthophyceae and Phaeophyceae. The cytology of these three classes is similar (Fig. 20.1). The cells have two membranes of chloroplast endoplasmic reticulum with the outer membrane of chloroplast E.R. continuous with the outer membrane of the nuclear envelope. The chloroplasts have a ring-shaped genophore and girdle lamellae. The flagella are inserted

Fig. 20.1 A filament and

zoospore of Phaeothamnion

polychrysis. Also included is the fine

structure of a zoospore.

HETEROKONTOPHYTA, PHAEOTHAMNIOPHYCEAE |

425 |

|

|

Fig. 20.2 Some algae classified in the

Phaeothamniophyceae.

laterally into the motile cells. The anterior tinsel flagellum has tripartite hairs that lack lateral filaments. The posterior flagellum lacks hairs. New daughter cells are formed by eleutheroschisis (parent cell wall is completely cast off and new daughter cell walls are formed). Vesicles under the plasma membrane appear similar to the physodes that occur in the Phaeophyceae. The Phaeothamniophyceae is the only class of algae where fucoxanthin and heteroxanthin occur together. Endogenous siliceous cysts (statospores) are not produced by these algae.

Phaeothamnion is a filamentous brown alga that produces zoospores that settle to produce new filaments (Fig. 20.1) (Andersen et al., 1998). Tetrachrysis occurs in environments such as peat ponds and has cells embedded in a common mucilage (Dop et al., 1980) (Fig. 20.2). Tetrasporopsis is a colonial freshwater alga that consists of a brown, gelatinous, bladdery sac (Entwisle and Andersen, 1990) (Fig. 20.2). Phaeoschizochlamys occurs among detritus or suspended between other freshwater algae. The cells occur in mucilage of different shapes up to 0.5 mm in

diameter (Fig. 20.2). The cells divide to form four autospores containing two chloroplasts.

REFERENCES

Andersen, R. A., Potter, D., Bidigare, R. R., Latasa, M., Rowar, K., and O’Kelly, C. J. (1998). Characterization and phylogenetic position of the enigmatic golden alga Phaeothamnion confervicola: ultrastructure, pigment composition and partial SSU rDNA sequence. J. Phycol. 34:286–98.

Bailey, J. C., Bidigare, R. R., Christensen, S. J., and Andersen, R. A. (1998). Phaeothamniophyceae classis nova: a new lineage of chromophytes based upon photosynthetic pigments, rbcL sequence analysis and ultrastructure. Protist 149:245–63.

Dop, A. J., Kosterman, Y., and van Oers, F. (1980). Coccoid and palmelloid benthic Chrysophyceae from the Netherlands. Acta Bot. Neerl. 29:87–102.

Entwisle, T. J., and Andersen, R. A. (1990). A reexamination of Tetrasporopsis (Chrysophyceae) and a description of Dermatochrysis gen. nov. (Chrysophyceae): a monostromatic algae lacking cells walls. Phycologia 29:263–74.