- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1 Posterior Compartment

- •2.2 Anterior Compartment

- •2.3 Middle Compartment

- •2.4 Perineal Body

- •3 Compartments

- •3.1 Posterior Compartment

- •3.1.1 Connective Tissue Structures

- •3.1.2 Muscles

- •3.1.3 Reinterpreted Anatomy and Clinical Relevance

- •3.2 Anterior Compartment

- •3.2.1 Connective Tissue Structures

- •3.2.2 Muscles

- •3.2.3 Reinterpreted Anatomy and Clinical Relevance

- •3.2.4 Important Vessels, Nerves, and Lymphatics of the Anterior Compartment

- •3.3 Middle Compartment

- •3.3.1 Connective Tissue Structures

- •3.3.2 Muscles

- •3.3.3 Reinterpreted Anatomy and Clinical Relevance

- •3.3.4 Important Vessels, Nerves, and Lymphatics of the Middle Compartment

- •4 Perineal Body

- •References

- •MR and CT Techniques

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2.1 Spasmolytic Medication

- •2.3.2 Diffusion-Weighted Imaging

- •2.3.3 Dynamic Contrast Enhancement

- •3 CT Technique

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Technical Disadvantages

- •3.4 Oral and Rectal Contrast

- •References

- •Uterus: Normal Findings

- •1 Introduction

- •References

- •1 Clinical Background

- •1.1 Epidemiology

- •1.2 Clinical Presentation

- •1.3 Embryology

- •1.4 Pathology

- •2 Imaging

- •2.1 Technique

- •2.2.1 Class I Anomalies: Dysgenesis

- •2.2.2 Class II Anomalies: Unicornuate Uterus

- •2.2.3 Class III Anomalies: Uterus Didelphys

- •2.2.4 Class IV Anomalies: Bicornuate Uterus

- •2.2.5 Class V Anomalies: Septate Uterus

- •2.2.6 Class VI Anomalies: Arcuate Uterus

- •2.2.7 Class VII Anomalies

- •References

- •Benign Uterine Lesions

- •1 Background

- •1.1 Uterine Leiomyomas

- •1.1.1 Epidemiology

- •1.1.2 Pathogenesis

- •1.1.3 Histopathology

- •1.1.4 Clinical Presentation

- •1.1.5 Therapy

- •1.1.5.1 Indications

- •1.1.5.2 Medical Therapy and Ablation

- •1.1.5.3 Surgical Therapy

- •1.1.5.4 Uterine Artery Embolization (UAE)

- •1.1.5.5 Magnetic Resonance-Guided Focused Ultrasound

- •2 Adenomyosis of the Uterus

- •2.1 Epidemiology

- •2.2 Pathogenesis

- •2.3 Histopathology

- •2.4 Clinical Presentation

- •2.5 Therapy

- •3 Imaging

- •3.2 Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- •3.2.1 Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Technique

- •3.2.2 MR Appearance of Uterine Leiomyomas

- •3.2.3 Locations, Growth Patterns, and Imaging Characteristics

- •3.2.4 Histologic Subtypes and Forms of Degeneration

- •3.2.5 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.2.6 MR Appearance of Uterine Adenomyosis

- •3.2.7 Locations, Growth Patterns, and Imaging Characteristics

- •3.2.8 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.3 Computed Tomography

- •3.3.1 CT Technique

- •3.3.2 CT Appearance of Uterine Leiomyoma and Adenomyosis

- •3.3.3 Atypical Appearances on CT and Differential Diagnosis

- •4.1 Indications

- •4.2 Technique

- •Bibliography

- •Cervical Cancer

- •1 Background

- •1.1 Epidemiology

- •1.2 Pathogenesis

- •1.3 Screening

- •1.4 HPV Vaccination

- •1.5 Clinical Presentation

- •1.6 Histopathology

- •1.7 Staging

- •1.8 Growth Patterns

- •1.9 Treatment

- •1.9.1 Treatment of Microinvasive Cervical Cancer

- •1.9.2 Treatment of Grossly Invasive Cervical Carcinoma (FIGO IB-IVA)

- •1.9.3 Treatment of Recurrent Disease

- •1.9.4 Treatment of Cervical Cancer During Pregnancy

- •1.10 Prognosis

- •2 Imaging

- •2.1 Indications

- •2.1.1 Role of CT and MRI

- •2.2 Imaging Technique

- •2.2.2 Dynamic MRI

- •2.2.3 Coil Technique

- •2.2.4 Vaginal Opacification

- •2.3 Staging

- •2.3.1 General MR Appearance

- •2.3.2 Rare Histologic Types

- •2.3.3 Tumor Size

- •2.3.4 Local Staging

- •2.3.4.1 Stage IA

- •2.3.4.2 Stage IB

- •2.3.4.3 Stage IIA

- •2.3.4.4 Stage IIB

- •2.3.4.5 Stage IIIA

- •2.3.4.6 Stage IIIB

- •2.3.4.7 Stage IVA

- •2.3.4.8 Stage IVB

- •2.3.5 Lymph Node Staging

- •2.3.6 Distant Metastases

- •2.4 Specific Diagnostic Queries

- •2.4.1 Preoperative Imaging

- •2.4.2 Imaging Before Radiotherapy

- •2.5 Follow-Up

- •2.5.1 Findings After Surgery

- •2.5.2 Findings After Chemotherapy

- •2.5.3 Findings After Radiotherapy

- •2.5.4 Recurrent Cervical Cancer

- •2.6.1 Ultrasound

- •2.7.1 Metastasis

- •2.7.2 Malignant Melanoma

- •2.7.3 Lymphoma

- •2.8 Benign Lesions of the Cervix

- •2.8.1 Nabothian Cyst

- •2.8.2 Leiomyoma

- •2.8.3 Polyps

- •2.8.4 Rare Benign Tumors

- •2.8.5 Cervicitis

- •2.8.6 Endometriosis

- •2.8.7 Ectopic Cervical Pregnancy

- •References

- •Endometrial Cancer

- •1.1 Epidemiology

- •1.2 Pathology and Risk Factors

- •1.3 Symptoms and Diagnosis

- •2 Endometrial Cancer Staging

- •2.1 MR Protocol for Staging Endometrial Carcinoma

- •2.2.1 Stage I Disease

- •2.2.2 Stage II Disease

- •2.2.3 Stage III Disease

- •2.2.4 Stage IV Disease

- •4 Therapeutic Approaches

- •4.1 Surgery

- •4.2 Adjuvant Treatment

- •4.3 Fertility-Sparing Treatment

- •5.1 Treatment of Recurrence

- •6 Prognosis

- •References

- •Uterine Sarcomas

- •1 Epidemiology

- •2 Pathology

- •2.1 Smooth Muscle Tumours

- •2.2 Endometrial Stromal Tumours

- •3 Clinical Background

- •4 Staging

- •5 Imaging

- •5.1 Leiomyosarcoma

- •5.2.3 Undifferentiated Uterine Sarcoma

- •5.3 Adenosarcoma

- •6 Prognosis and Treatment

- •References

- •1.1 Anatomical Relationships

- •1.4 Pelvic Fluid

- •2 Developmental Anomalies

- •2.1 Congenital Abnormalities

- •2.2 Ovarian Maldescent

- •3 Ovarian Transposition

- •References

- •1 Introduction

- •4 Benign Adnexal Lesions

- •4.1.1 Physiological Ovarian Cysts: Follicular and Corpus Luteum Cysts

- •4.1.1.1 Imaging Findings in Physiological Ovarian Cysts

- •4.1.1.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.1.2 Paraovarian Cysts

- •4.1.2.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.1.2.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.1.3 Peritoneal Inclusion Cysts

- •4.1.3.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.1.3.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.1.4 Theca Lutein Cysts

- •4.1.4.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.1.4.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.1.5 Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

- •4.1.5.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.1.5.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.2.1 Cystadenoma

- •4.2.1.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.2.1.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •4.2.2 Cystadenofibroma

- •4.2.2.1 Imaging Features

- •4.2.3 Mature Teratoma

- •4.2.3.1 Mature Cystic Teratoma

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •4.2.3.2 Monodermal Teratoma

- •Imaging Findings

- •4.2.4 Benign Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors

- •4.2.4.1 Fibroma and Thecoma

- •Imaging Findings

- •4.2.4.2 Sclerosing Stromal Tumor

- •Imaging Findings

- •4.2.5 Brenner Tumors

- •4.2.5.1 Imaging Findings

- •4.2.5.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •5 Functioning Ovarian Tumors

- •References

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1 Context

- •2.2.2 Indications According to Simple Rules

- •References

- •CT and MRI in Ovarian Carcinoma

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1 Familial or Hereditary Ovarian Cancers

- •3 Screening for Ovarian Cancer

- •5 Tumor Markers

- •6 Clinical Presentation

- •7 Imaging of Ovarian Cancer

- •7.1.2 Peritoneal Carcinomatosis

- •7.1.3 Ascites

- •7.3 Staging of Ovarian Cancer

- •7.3.1 Staging by CT and MRI

- •Imaging Findings According to Tumor Stages

- •Value of Imaging

- •7.3.2 Prediction of Resectability

- •7.4 Tumor Types

- •7.4.1 Epithelial Ovarian Cancer

- •High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer

- •Low-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer

- •Mucinous Epithelial Ovarian Cancer

- •Endometrioid Ovarian Carcinomas

- •Clear Cell Carcinomas

- •Imaging Findings of Epithelial Ovarian Cancers

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •Borderline Tumors

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •Recurrent Ovarian Cancer

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •Value of Imaging

- •Malignant Germ Cell Tumors

- •Dysgerminomas

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •Immature Teratomas

- •Imaging Findings

- •Malignant Transformation in Benign Teratoma

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •Sex-Cord Stromal Tumors

- •Granulosa Cell Tumors

- •Imaging Findings

- •Sertoli-Leydig Cell Tumor

- •Imaging Findings

- •Ovarian Lymphoma

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •7.4.3 Ovarian Metastases

- •Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •7.5 Fallopian Tube Cancer

- •7.5.1 Imaging Findings

- •Differential Diagnosis

- •References

- •Endometriosis

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1 Sonography

- •3 MR Imaging Findings

- •References

- •Vagina and Vulva

- •1 Introduction

- •3.1 CT Appearance

- •3.2 MRI Protocol

- •3.3 MRI Appearance

- •4.1 Imperforate Hymen

- •4.2 Congenital Vaginal Septa

- •4.3 Vaginal Agenesis

- •5.1 Vaginal Cysts

- •5.1.1 Gardner Duct Cyst (Mesonephric Cyst)

- •5.1.2 Bartholin Gland Cyst

- •5.2.1 Vaginal Infections

- •5.2.1.1 Vulvar Infections

- •5.2.1.2 Vulvar Thrombophlebitis

- •5.3 Vulvar Trauma

- •5.4 Vaginal Fistula

- •5.5 Post-Radiation Changes

- •5.6 Benign Tumors

- •6.1 Vaginal Malignancies

- •6.1.1 Primary Vaginal Carcinoma

- •6.1.1.1 MRI Findings

- •6.1.1.2 Lymph Node Drainage

- •6.1.1.3 Recurrence and Complications

- •6.1.2 Non-squamous Cell Carcinomas of the Vagina

- •6.1.2.1 Adenocarcinoma

- •6.1.2.2 Melanoma

- •6.1.2.3 Sarcomas

- •6.1.2.4 Lymphoma

- •6.2 Vulvar Malignancies

- •6.2.1 Vulvar Carcinoma

- •6.2.2 Melanoma

- •6.2.3 Lymphoma

- •6.2.4 Aggressive Angiomyxoma of the Vulva

- •7 Vaginal Cuff Disease

- •7.1 MRI Findings

- •8 Foreign Bodies

- •References

- •Imaging of Lymph Nodes

- •1 Background

- •3 Technique

- •3.1.1 Intravenous Unspecific Contrast Agents

- •3.1.2 Intravenous Tissue-Specific Contrast Agents

- •References

- •1 Introduction

- •2.1.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.1.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •2.1.3 Value of Imaging

- •2.2 Pelvic Inflammatory

- •2.2.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.3 Hydropyosalpinx

- •2.3.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.3.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •2.4 Tubo-ovarian Abscess

- •2.4.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.4.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •2.4.3 Value of Imaging

- •2.5 Ovarian Torsion

- •2.5.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.5.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •2.5.3 Diagnostic Value

- •2.6 Ectopic Pregnancy

- •2.6.1 Imaging Findings

- •2.6.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •2.6.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.1 Pelvic Congestion Syndrome

- •3.1.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.1.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.1.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.2 Ovarian Vein Thrombosis

- •3.2.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.2.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.2.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.3 Appendicitis

- •3.3.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.3.2 Value of Imaging

- •3.4 Diverticulitis

- •3.4.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.4.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.4.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.5 Epiploic Appendagitis

- •3.5.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.5.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.5.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.6 Crohn’s Disease

- •3.6.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.6.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.6.3 Value of Imaging

- •3.7 Rectus Sheath Hematoma

- •3.7.1 Imaging Findings

- •3.7.2 Differential Diagnosis

- •3.7.3 Value of Imaging

- •References

- •MRI of the Pelvic Floor

- •1 Introduction

- •2 Imaging Techniques

- •3.1 Indications

- •3.2 Patient Preparation

- •3.3 Patient Instruction

- •3.4 Patient Positioning

- •3.5 Organ Opacification

- •3.6 Sequence Protocols

- •4 MR Image Analysis

- •4.1 Bony Pelvis

- •5 Typical Findings

- •5.1 Anterior Compartment

- •5.2 Middle Compartment

- •5.3 Posterior Compartment

- •5.4 Levator Ani Muscle

- •References

- •Evaluation of Infertility

- •1 Introduction

- •2 Imaging Techniques

- •2.1 Hysterosalpingography

- •2.1.1 Cycle Considerations

- •2.1.2 Technical Considerations

- •2.1.3 Side Effects and Complications

- •2.1.5 Pathological Findings

- •2.1.6 Limitations of HSG

- •2.2.1 Cycle Considerations

- •2.2.2 Technical Considerations

- •2.2.2.1 Normal and Abnormal Anatomy

- •2.2.3 Accuracy

- •2.2.4 Side Effects and Complications

- •2.2.5 Limitations of Sono-HSG

- •2.3 Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- •2.3.1 Indications

- •2.3.2 Technical Considerations

- •2.3.3 Limitations

- •3 Ovulatory Dysfunction

- •4 Pituitary Adenoma

- •5 Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome

- •7 Uterine Disorders

- •7.1 Müllerian Duct Anomalies

- •7.1.1 Class I: Hypoplasia or Agenesis

- •7.1.2 Class II: Unicornuate

- •7.1.3 Class III: Didelphys

- •7.1.4 Class IV: Bicornuate

- •7.1.5 Class V: Septate

- •7.1.6 Class VI: Arcuate

- •7.1.7 Class VII: Diethylstilbestrol Related

- •7.2 Adenomyosis

- •7.3 Leiomyoma

- •7.4 Endometriosis

- •References

- •MR Pelvimetry

- •1 Clinical Background

- •1.3.1 Diagnosis

- •1.3.2.1 Cephalopelvic Disproportion

- •1.3.4 Inadequate Progression of Labor due to Inefficient Contraction (“the Powers”)

- •2.2 Palpation of the Pelvis

- •3 MR Pelvimetry

- •3.2 MR Imaging Protocol

- •3.3 Image Analysis

- •3.4 Reference Values for MR Pelvimetry

- •5 Indications for Pelvimetry

- •References

- •MR Imaging of the Placenta

- •2 Imaging of the Placenta

- •3 MRI Protocol

- •4 Normal Appearance

- •4.1 Placenta Variants

- •5 Placenta Adhesive Disorders

- •6 Placenta Abruption

- •7 Solid Placental Masses

- •9 Future Directions

- •References

- •Erratum to: Endometrial Cancer

Endometrial Cancer |

183 |

|

|

≤5 mm is associated with the absence of endometrial cancer (Gupta et al. 2002). This cut-off value should also be used in women under hormone replacement therapy and under tamoxifen (Bennet et al. 2011).

In symptomatic patients in premenopausal age, an upper threshold of normal endometrial thickness is more difficult to establish due to its variations during the menstrual cycle. In this group of women, the assessment of the endometrium should be performed during the early first half of the menstrual cycle (Bennet et al. 2011). In these women, an endometrial thickness >16 mm has shown to have a sensitivity of 67 % and a specificity of 75 % for detecting endometrial abnormalities (Bennet et al. 2011; Hulka et al. 1994). A heterogeneous endometrium or an area of focal thickness should be also further investigated (Bennet et al. 2011; Goldstein et al. 2001).

If the endometrium is thickened or heterogeneous, a sample of the endometrium must be undertaken to establish a definite histopathological diagnosis. In these cases a hysteroscopy with biopsy or resection should be performed.

Before treatment, the initial evaluation should include a medical history, a physical and gynecological examination, a complete blood count, and a chest radiograph (Koh et al. 2014).

If the age of the onset of the disease is <50 years and if there is history of familiar colorectal or endometrial cancer, screening for genetic mutations should be performed (Koh et al. 2014).

Women with Lynch syndrome, without endometrial cancer, should be screened annually with an endometrial biopsy (Koh et al. 2014; Järvinen et al. 2009; Meyer et al. 2009). Prophylactic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingoophorectomy may be considered in these patients (Koh et al. 2014; Schmeler et al. 2006).

2\ Endometrial Cancer Staging

Endometrial carcinoma is staged with the International Federation of Gynaecology Obstetrics (FIGO) system, which was last revised

Table 3 Endometrial Cancer Staging: FIGOa 2009

Stage I—The tumor is confined to the uterine corpus

IA—Absence or invasion of <50 % of the myometrium

IB—Invasion of ≥50 % of the myometrium

Stage II—The tumor invades the cervical stroma, but not beyond the uterus

Stage III—There is local or regional involvement

IIIA—The tumor invades the serosa and/or the adnexa

IIIB—Presence of vaginal and/or parametrial involvement

IIIC—Presence of pelvic or para-aortic lymphadenopathies

IIIC1—Presence of pelvic lymphadenopathies

IIIC2—Presence of para-aortic lymphadenopathies, with or without pelvic lymphadenopathies

Stage IV—The tumor invades the bladder mucosa and/ or the intestinal mucosa, and/or there are distant metastases

IVA—The tumor invades the bladder mucosa and/or the intestinal mucosa

IVB—Presence of distant metastases, including abdominal metastases and/or inguinal lymphadenopathies.

Adapted from Pecorelli (2009)

aFIGO International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics

in 2009 (Table 3) (Creasman 2009; Pecorelli 2009). This classification defines that endometrial carcinoma is staged on the basis of surgicopathological findings.

The complete surgical staging procedure implies hysterectomy with bilateral salpingooophorectomy, assessment of the abdominal cavity with biopsies of suspicious peritoneal lesions, cytology of peritoneal washings, and pelvic and retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy (Koh et al. 2014). In patients with serous carcinoma, clearcell carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma, the surgical staging procedure should be the same as for ovarian cancer (Koh et al. 2014).

The FIGO 2009 staging classification is as follows (Table 3) (Pecorelli 2009):

In stage I, the tumor is confined to the uterus. This stage is subdivided in two substages: stage IA (the tumor invades <50 % of the myometrium) and stage IB (the tumor invades ≥50 % of the myometrium).

184 |

M. Horta and T.M. Cunha |

|

|

In stage II, the tumor invades the cervical stroma, but not beyond the uterus.

Stage III is subdivided into three substages. In stage IIIA, the tumor invades the serosa or/and the adnexa (direct extension or metastasis). In stage IIIB, there is involvement of the parametria and/or the vagina (direct extension or metastasis). In stage IIIC, there is lymph node involvement (IIIC1 if there are positive pelvic lymph nodes and IIIC2 if there are positive para-aortic lymph nodes).

Stage IV is also subdivided into two substages. The tumor is in stage IVA if there is mucosal invasion of the bladder or/and the bowel and it is in stage IVB if there are distant metastasis including abdominal metastasis and/or the presence of positive inguinal lymph nodes.

MR imaging is not considered in the FIGO staging of endometrial carcinoma, but due to its high contrast resolution and reproducibility, it has an important role in the preoperative staging of the disease. Thus, it is crucial for tailoring the surgical approach to these patients.

There is still no consensus on whether complete surgical staging with primary pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenopathy should be performed at stage I, namely, in patients with low recurrence risk (Bonatti et al. 2015; Todo et al. 2010; May et al. 2010). However, it is known that the tumor histological type and grade, the presence of myometrial invasion ≥50 %, and the presence of lymphovascular space invasion correlate with the presence of lymph node metastasis and with overall survival (Rechichi et al. 2010; Sala et al. 2013; Boronow 1990; Larson et al. 1996). From these features, only the histological type and grade can be assessed preoperatively without imaging. Nonetheless, discrepancies of up to 15 % between the preand postoperative tumoral histopathological results have been described (Sala et al. 2013; Frei et al. 2000).

MR can accurately determine the depth of myometrial invasion. Therefore, in conjunction with the histopathological grade it may be used to select the patients that might be candidates for pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, precluding surgery in low-risk patients, thus avoiding the morbidities associated with this procedure.

Presence of lymph node metastases has been reported in more than 30 % of the cases of endometrial cancer with ≥50 % of myometrial invasion and in only 5 % of cases when the tumor invades <50 % of the myometrium (Larson et al. 1996; Gallego et al. 2014).

Lymphovascular invasion is generally assessed postoperatively. It is related not only to the likelihood of lymph node involvement, but with tumor relapse and poor survival (Sala et al. 2013; Fujii et al. 2015; Briët et al. 2005). Not many studies have addressed the role of MR in diagnosing lymphovascular space involvement. However, a study by Nougaret et al. showed that whole tumor volume and ADC could be useful in its prediction (Nougaret et al. 2015).

Cervical stromal invasion is also associated with lymph node metastasis and poor survival. MR can accurately diagnose cervical stromal invasion and parametrial invasion. This is particularly important so surgeons can avoid cutting through the tumor and thus perform an extensive resection (Sala et al. 2013).

Moreover, MR is helpful is diagnosing advanced disease involving the adnexa and the peritoneum, which generally are contraindications to laparoscopic and robotic surgery (Sala et al. 2013; Venkat et al. 2012; Amant et al. 2007). Other extra-uterine coexistent pathologies can also be diagnosed that may help determining the surgical approach.

Therefore, MR is useful not only in planning surgical treatment but also in selecting more advanced and difficult surgical cases that should be guided to specialized oncologic centers.

MR is also useful in determining the origin (cervical or endometrial) of a biopsy proven adenocarcinoma (Fig. 2). Vargas and colleagues showed that by assessing the epicenter of the tumor, the endometrial versus the cervical origin of an adenocarcinoma could be determined with an accuracy of 85–88 % (Vargas et al. 2011). Furthermore, endometrial thickening, expansion of the endometrial cavity by a mass, and the presence of a tumor invading the myometrium may aid the discrimination between these two types of tumors (Haider et al. 2006). This distinction is particularly important, because early stage cervical adenocarcinomas are

Endometrial Cancer |

185 |

|

|

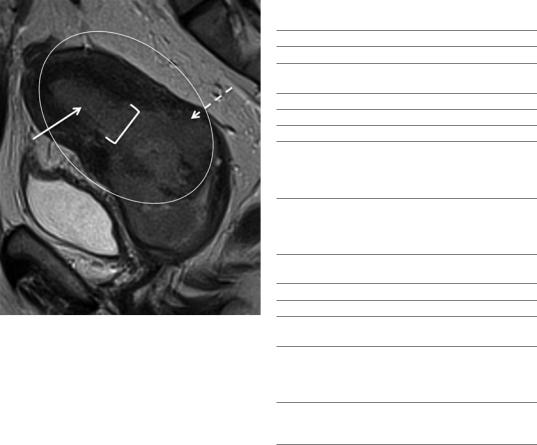

Fig. 2 Endometrial carcinoma that invades the cervical stroma in a 53-year-old woman. Sagittal T2-weighted image. Distinction between endometrial and cervical origin of an adenocarcinoma may be challenging. Radiologists should look for the epicenter of the tumor (>50 %) (circle), and other signs that may help defining endometrial origin, such as endometrial thickness (arrow), expansion of the uterine cavity by a mass (squared brackets), and invasion of the myometrium (dashed arrow)

Table 4 MR protocol scheme for endometrial cancer staging

MRI protocol for endometrial cancer staging

Abdomen

T2 FSE axial (6 mm/1 mm)—from the diaphragm to the iliac crests

Axial DWI and the respective ADC maps (6 mm)

Pelvis

T1 FSE axial (5 mm/0.5 mm)

T2 FSE axial (5 mm/0.5 mm); T2 FSE sagittal

(4 mm/0.4 mm); T2 FSE axial oblique of the uterine corpus (perpendicular to the uterine cavity;

4 mm/0.4 mm)

Dynamic contrast-enhanced study in the axial oblique plane of the uterine corpus: 3D T1, FS preand postcontrast administration, five acquisition phases (until 150 s; 2 mm)

Axial DWI and the respective ADC maps (5 mm/0.5 mm)

Protocol variants

If there is suspicion of cervix invasion:

T2 FSE axial oblique of the uterine cervix (perpendicular to the cervical canal; 4 mm/0.4 mm)

Dynamic contrast-enhanced study in the sagittal plane: 3D T1, FS preand postcontrast administration, five acquisition phases (until 150 s; 2 mm)

Axial oblique plane of the uterine cervix postcontrast injection 3D T1, FS in late phase (4 min; 2 mm)

treated with surgery, advanced stage cervical adenocarcinomas are treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy and endometrial carcinomas are treated primarily with surgery.

Although fertility-sparing progesterone therapy is not the standard of care for endometrial cancers, it might be considered according to patients request in treatment of low-grade endometrial cancers that do not invade the myometrium. In these cases, MR is essential in defining which patients are candidates to this approach.

2.1\ MR Protocol for Staging Endometrial Carcinoma

In our institution the MR protocol for staging endometrial carcinoma is as follows (Table 4):

Patients are advised to fast 4–6 h before the procedure. A fast acting laxative enema to clean

the bowel is administered the day before the exam and during the morning of the exam. Patients are encouraged to void before the examination since a full bladder degrades the quality of T2-weighted images.

In order to reduce bowel peristalsis and hence improve image quality, 1 mg of glucagon intravenous is administered before the exam. Alternatively, 20 mg or 40 mg of hyoscine butylbromide intramuscular/intravenous can be administered.

Patients are advised to avoid the use of vaginal tampon.

MR imaging can either be performed in a 1.5 T or a 3 T MR machine. 3 T MR has been not shown to offer significant benefit over 1.5 T MR in the evaluation of endometrial cancer, since 3 T MR is more prone to susceptibility and chemicalshift artifacts that impair the image quality (Wakefield et al. 2013; Haldorsen and Salvesen 2012; Hori et al. 2013).

186 |

M. Horta and T.M. Cunha |

|

|

a |

c |

b |

d |

Fig. 3 (a, b) Axial oblique plane of the uterine corpus (perpendicular to the uterine cavity); (c, d) axial oblique plane of the uterine cervix (perpendicular to the cervical canal)

A pelvic phase array is used along with ante- |

(6 mm, b-values—0, 500, 1000 |

s/mm2) and the |

|

rior and superior saturation bands. |

respective ADC maps should also be obtained. |

||

The patient should be placed in a supine posi- |

Evaluation of the pelvis should be performed |

||

tion for the whole exam. However, prone position |

with axial fast spin-echo T1-weighted images |

||

may be used in uncooperative patients. |

(5 mm/0.5 mm), axial fast spin-echo T2-weighted |

||

Axial imaging of the abdomen (from |

images (5 mm/0.5 mm), and sagittal fast spin- |

||

diaphragm |

to iliac crests) should be per- |

echo T2-weighted images (4 mm/0.4 mm). |

|

formed for the evaluation of advanced |

Fast spin-echo T2-weighted axial oblique |

||

disease, with fast recovery, fast spin-echo T2- |

images (perpendicular to the |

uterine cavity, |

|

weighted images (6 mm/1 mm, breath-hold). Abdo |

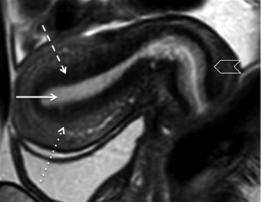

4 mm/0.4 mm) are helpful in assessing myome- |

||

minal axial |

diffusion-weighted images (DWI) |

trial invasion (Fig. 3). |

|

Endometrial Cancer |

187 |

|

|

The dynamic contrast-enhanced MR images are obtained after the injection of 0.1 mmol/kg of gadolinium at a rate of 2 mL/s. In our institution, images are acquired using a 3D-recalled echo fatsuppressed T1-weighted sequence, preand postcontrast injection during five acquisition phases in the axial-oblique plane (perpendicular to the uterine cavity), until 150 s (2 mm). The dynamic study tends to be avoided in patients with renal impairment.

DWI study (b-values—0, 600, 1000 s/mm2, 5 mm/0.5 mm) and the respective ADC maps are performed in the axial plane.

If there is suspicion of cervix invasion, axial oblique of the cervix fast spin-echo T2-weighted images (perpendicular to the cervical canal, 4 mm/0.4 mm) are obtained to evaluate parametrial invasion (Fig. 3). In these cases, the dynamic study should be performed in the sagittal plane using a 3D-reccaled echo fat-suppressed T1-weighted sequence, preand postcontrast injection during five acquisition phases until 150 s (2 mm). Furthermore, axial oblique of the cervix (perpendicular to cervical canal) postcontrast injection 3D-reccaled echo fat-suppressed T1-weighted images are obtained in a late phase (4 min, 2 mm), to better assess cervical stromal invasion (Fig. 3).

2.2\ MR Findings According

to the Stage of Endometrial

Carcinoma

On conventional imaging, the normal uterus anatomy is better depicted on T2-weighted images. The endometrium tends to be hyperintense, the junctional zone is hypointense and the outer myometrium shows intermediate intensity (Fig. 4).

Endometrial cancer is isointense to the endometrium on T1-weighted images and it most frequently shows heterogeneous moderate to high-signal intensity on T2-weighted images. However, it can also show low-signal intensity on T2-weighted images (Fig. 5).

On DCE-MR, in the arterial phase (≈30 s) endometrial tumors enhance earlier than does the

Fig. 4 Normal uterine T2-weighted anatomy. Sagittal T2-weighted image. Hyperintense endometrium (arrow); hypointense junctional zone (dashed arrow); outer myometrium showing intermediate intensity (dotted line); hypointense cervical stroma (arrowhead)

normal endometrium, as this is the most adequate sequence to depict small endometrial tumors confined to the endometrium. At the equilibrium phase (≈120–180 s), tumors tend to be hypointense relative to the myometrium. However, they can remain isointense and a minority can even be hyperintense (Figs. 5 and 6).

On DWI-MR the tumors usually show restricted diffusion (hyperintensity on high b-value sequences and hypointensity on the respective ADC map) (Fig. 6). ADC values have shown to be significantly lower in endometrial carcinoma than in normal endometrium and benign conditions such as endometrial polyps and submucosal leiomyomas (Fujii et al. 2008; Tamai et al. 2007; Takeuchi et al. 2009; Rechichi et al. 2011) (Fig. 7).Therefore, this functional sequence can be helpful in diagnosing an endometrial tumor when biopsy cannot be easily performed (i.e., in the case of cervical stenosis) or when the histopathological diagnosis is not conclusive. Cross-reference with conventional sequences is, however, mandatory to avoid pitfalls, since restricted diffusion may be present also in retained secretions in the endometrial cavity.

Several studies have shown that there is no relation between the tumor grade, aggressiveness, and ADC values (Rechichi et al. 2011;