Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Your first priority for a patient with apneustic respirations is to ensure adequate ventilation. You’ll need to insert an artificial airway and administer oxygen until mechanical ventilation can begin. Next, thoroughly evaluate the patient’s neurologic status, using a standardized tool such as the Glasgow Coma Scale. Finally, obtain a brief patient history from a family member, if possible.

Medical Causes

Pontine lesions. Apneustic respirations usually result from extensive damage to the upper or lower pons due to infarction, hemorrhage, herniation, severe infection, tumor, or trauma. Typically, these respirations are accompanied by profound stupor or coma; pinpoint midline pupils; ocular bobbing (a spontaneous downward jerk, followed by a slow drift up to midline); quadriplegia or, less commonly, hemiplegia with the eyes pointing toward the weak side; a positive Babinski’s reflex; negative oculocephalic and oculovestibular reflexes; and, possibly, decorticate posture.

Special Considerations

Constantly monitor the patient’s neurologic and respiratory status. Watch for prolonged periods of apnea or signs of neurologic deterioration. Monitor the patient’s arterial blood gas levels, or use a pulse oximetry device. If appropriate, prepare him for neurologic tests, such as EEG and computed tomography scanning or magnetic resonance imaging.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient and his family about his condition and treatment options, and explain all diagnostic tests and procedures.

Pediatric Pointers

In young children, avoid using the Glasgow Coma Scale because it requires verbal responses and assumes a certain level of language development.

REFERENCES

Chou, C. H., Lin, G. M., Ku, C. H., & Chang, F. Y. (2010) . Comparison of the APACHE II, GCS and MRC scores in predicting outcomes in patients with tuberculous meningitis. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 14(1), 86–92.

Looser, R. R., Metzenthin, P. , Helfrich, T. S., Kudielka, B. M., Loerbroks, A. , Thayer, J. F. , & Fischer, J. E. (2010) . Cortisol is significantly correlated with cardiovascular responses during high levels of stress in critical care personnel. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72(3), 281–289.

Arm Pain

Arm pain usually results from musculoskeletal disorders, but it can also stem from neurovascular or cardiovascular disorders. (See Causes of Local Pain.) In some cases, it may be referred pain from

another area, such as the chest, neck, or abdomen. Its location, onset, and character provide clues to its cause. The pain may affect the entire arm or only the upper arm or forearm. It may arise suddenly or gradually and may be constant or intermittent. Arm pain can be described as sharp or dull, burning or numbing, and shooting or penetrating. Diffuse arm pain, however, may be difficult to describe, especially if it isn’t associated with injury.

Causes of Local Pain

Various disorders cause hand, wrist, elbow, or shoulder pain. In some disorders, pain may radiate from the injury site to other areas.

HAND PAIN

Arthritis

Buerger’s disease

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Dupuytren’s contracture

Elbow tunnel syndrome

Fracture

Ganglion

Infection

Occlusive vascular disease

Radiculopathy

Raynaud’s disease

Shoulder-hand syndrome (reflex sympathetic dystrophy)

Sprain or strain

Thoracic outlet syndrome

Trigger finger

WRIST PAIN

Arthritis

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Fracture

Ganglion

Sprain or strain

Tenosynovitis (de Quervain’s disease)

ELBOW PAIN

Arthritis

Bursitis

Dislocation

Fracture

Lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow)

Tendinitis

Ulnar neuritis

SHOULDER PAIN

Acromioclavicular separation

Acute pancreatitis

Adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder)

Angina pectoris

Arthritis

Bursitis

Cholecystitis or cholelithiasis

Clavicle fracture

Diaphragmatic pleurisy

Dislocation

Dissecting aortic aneurysm

Gastritis

Humeral neck fracture

Infection

Pancoast’s syndrome

Perforated ulcer

Pneumothorax

Ruptured spleen (left shoulder)

Shoulder-hand syndrome

Subphrenic abscess

Tendinitis

History and Physical Examination

If the patient reports arm pain after an injury, take a brief history of the injury from the patient. Then, quickly assess him for severe injuries requiring immediate treatment. If you’ve ruled out severe injuries, check pulses, capillary refill time, sensation, and movement distal to the affected area because circulatory impairment or nerve injury may require immediate surgery. Inspect the arm for deformities, assess the level of pain, and immobilize the arm to prevent further injury.

If the patient reports continuous or intermittent arm pain, ask him to describe it and to relate when it began. Is the pain associated with repetitive or specific movements or positions? Ask him to point out other painful areas because arm pain may be referred. For example, arm pain commonly accompanies the characteristic chest pain of myocardial infarction, and right shoulder pain may be referred from the right upper quadrant abdominal pain of cholecystitis. Ask the patient if the pain worsens in the morning or in the evening, if it prevents him from performing his job, and if it restricts movement. Also ask if heat, rest, or drugs relieve it. Finally, ask about preexisting illnesses, a family history of gout or arthritis, and current drug therapy.

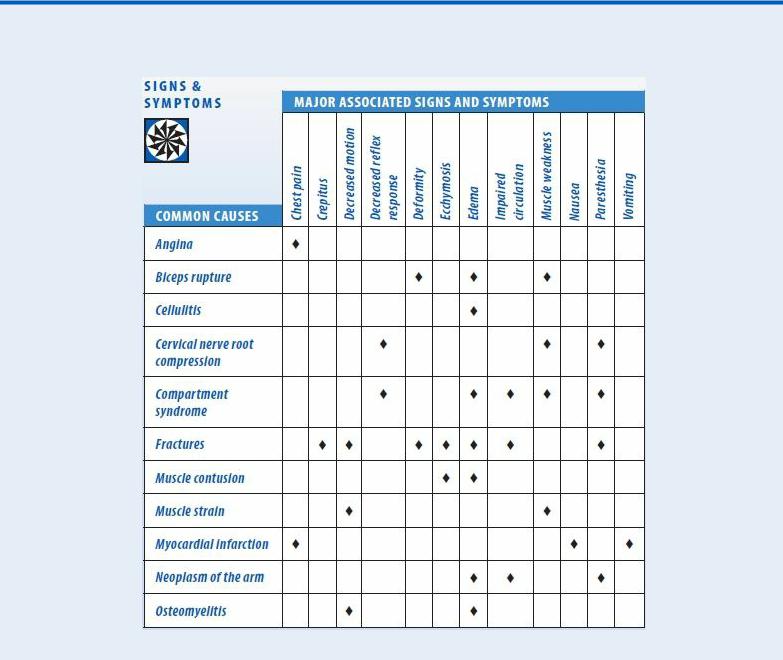

Arm Pain: Common Causes and Associated Findings

Next, perform a focused examination. Observe the way the patient walks, sits, and holds his arm. Inspect the entire arm, comparing it with the opposite arm for symmetry, movement, and muscle atrophy. (It’s important to know if the patient is rightor left-handed.) Palpate the entire arm for swelling, nodules, and tender areas. In both arms, compare active range of motion, muscle strength, and reflexes.

If the patient reports numbness or tingling, check his sensation to vibration, temperature, and pinprick. Compare bilateral hand grasps and shoulder strength to detect weakness.

If a patient has a cast, splint, or restrictive dressing, check for circulation, sensation, and mobility distal to the dressing. Ask the patient about edema and if the pain has worsened within the last 24 hours.

Examine the neck for pain on motion, point tenderness, muscle spasms, or arm pain when the neck is extended with the head toward the involved side. (See Arm Pain: Common Causes and Associated Findings.)

Medical Causes

Angina. Angina may cause inner arm pain as well as chest and jaw pain. Typically, the pain follows exertion and persists for a few minutes. Accompanied by dyspnea, diaphoresis, and apprehension, the pain is relieved by rest or vasodilators such as nitroglycerin.

Biceps rupture. Rupture of the biceps after excessive weight lifting or osteoarthritic degeneration of bicipital tendon insertion at the shoulder can cause pain in the upper arm. Forearm flexion and supination aggravate the pain. Other signs and symptoms include muscle weakness, deformity, and edema.

Cellulitis. Typically, cellulitis affects the legs, but it can also affect the arms. It produces pain as well as redness, tenderness, edema and, at times, fever, chills, tachycardia, headache, and hypotension. Cellulitis usually follows an injury or insect bite.

Cervical nerve root compression. Compression of the cervical nerves supplying the upper arm produces chronic arm and neck pain, which may worsen with movement or prolonged sitting. The patient may also experience muscle weakness, paresthesia, and decreased reflex response.

Compartment syndrome. Severe pain with passive muscle stretching is the cardinal symptom of compartment syndrome. It may also impair distal circulation and cause muscle weakness, decreased reflex response, paresthesia, and edema. Ominous signs include paralysis and an absent pulse.

Fractures. In fractures of the cervical vertebrae, humerus, scapula, clavicle, radius, or ulna, pain can occur at the injury site and radiate throughout the entire arm. Pain at a fresh fracture site is intense and worsens with movement. Associated signs and symptoms include crepitus, felt and heard from bone ends rubbing together (don’t attempt to elicit this sign); deformity, if bones are misaligned; local ecchymosis and edema; impaired distal circulation; paresthesia; and decreased sensation distal to the injury site. Fractures of the small wrist bones can manifest with pain and swelling several days after the trauma.

Muscle contusion. Muscle contusion may cause generalized pain in the area of injury. It may also cause local swelling and ecchymosis.

Muscle strain. Acute or chronic muscle strain causes mild to severe pain with movement. The resultant reduction in arm movement may cause muscle weakness and atrophy.

Myocardial infarction (MI). An MI is a life-threatening disorder in which the patient may complain of left arm pain as well as deep and crushing chest pain. He may display weakness, pallor, nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, altered blood pressure, tachycardia, dyspnea, and feelings of apprehension or impending doom.

Neoplasms of the arm. Neoplasms of the arm produce continuous, deep, and penetrating arm pain that worsens at night. Occasionally, redness and swelling accompany arm pain; later, skin breakdown, impaired circulation, and paresthesia may occur.

Osteomyelitis. Osteomyelitis typically begins with vague and evanescent localized arm pain and fever and is accompanied by local tenderness, painful and restricted movement and, later, swelling. Associated findings include malaise and tachycardia.

Special Considerations

If you suspect a fracture, apply a sling or splint to immobilize the arm, and monitor the patient for worsening pain, numbness, or decreased circulation distal to the injury site. Also, monitor the patient’s vital signs, and be alert for tachycardia, hypotension, and diaphoresis. Withhold food, fluids, and analgesics until potential fractures are evaluated. Promote the patient’s comfort by

elevating his arm and applying ice. Clean abrasions and lacerations, and apply dry, sterile dressings, if necessary. Also, prepare the patient for X-rays or other diagnostic tests.

Patient Counseling

Explain the signs and symptoms of an ischemic event and of circulatory impairment caused by a tight cast.

Pediatric Pointers

In children, arm pain commonly results from fractures, muscle sprain, muscular dystrophy, or rheumatoid arthritis. In young children especially, the exact location of the pain may be difficult to establish. Watch for nonverbal clues, such as wincing or guarding.

If the child has a fracture or sprain, obtain a complete account of the injury. Closely observe interactions between the child and his family, and don’t rule out the possibility of child abuse.

Geriatric Pointers

Elderly patients with osteoporosis may experience fractures from simple trauma or even from heavy lifting or unexpected movements. They’re also prone to degenerative joint disease that can involve several joints in the arm or neck.

REFERENCES

Deane, L., Giele, H., & Johnson, K. (2012). Thoracic outlet syndrome. British Medical Journal, 345, e7373.

Giummarra, M. J., & Moseley, G. L. (2011). Phantom limb pain and bodily awareness: Current concepts and future directions. Current Opinions in Anaesthesiology, 24, 524–531.

Asterixis [Liver flap, flapping tremor]

A bilateral, coarse movement, asterixis is characterized by sudden relaxation of muscle groups holding a sustained posture. This elicited sign is most commonly observed in the wrists and fingers, but may also appear during any sustained voluntary action. Typically, it signals hepatic, renal, or pulmonary disease.

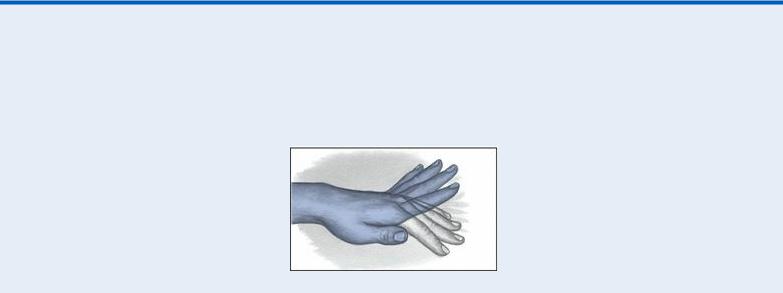

Recognizing Asterixis

With asterixis, the patient’s wrists and fingers are observed to “flap” because there’s a brief, rapid relaxation of dorsiflexion of the wrist.

To elicit asterixis, have the patient extend his arms, dorsiflex his wrists, and spread his fingers (or do this for him, if necessary). Briefly observe him for asterixis. Alternatively, if the patient has a decreased level of consciousness (LOC) but can follow verbal commands, ask him to squeeze two of your fingers. Consider rapid clutching and unclutching indications of asterixis. Or elevate the patient’s leg off the bed, and dorsiflex the foot. Briefly check for asterixis in the ankle. If the patient can tightly close his eyes and mouth, watch for irregular tremulous movements of the eyelids and corners of the mouth. If he can stick out his tongue, observe the patient for continuous quivering. (See

Recognizing Asterixis.)

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Because asterixis may signal serious metabolic deterioration, quickly evaluate the patient’s neurologic status and vital signs. Compare these data with baseline measurements, and watch carefully for acute changes. Continue to closely monitor his neurologic status, vital signs, and urine output.

Watch for signs of respiratory insufficiency, and be prepared to provide endotracheal intubation and ventilatory support. Also, be alert for complications of end-stage hepatic, renal, or pulmonary disease.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient has hepatic disease, assess him for early indications of hemorrhage, including restlessness, tachypnea, and cool, moist, pale skin. (If the patient is jaundiced, check for pallor in the conjunctiva and mucous membranes of the mouth.)

It’s important to recognize that hypotension, oliguria, hematemesis, and melena are late signs of hemorrhage. Prepare to insert a large-bore I.V. line for fluid and blood replacement. Position the patient flat in bed with his legs elevated 20 degrees. Begin or continue to administer oxygen.

If the patient has renal disease, briefly review the therapy he has received. If he’s on dialysis, ask about the frequency of treatments to help gauge the severity of disease. Question a family member if the patient’s LOC is significantly decreased.

Then, assess the patient for hyperkalemia and metabolic acidosis. Look for tachycardia, nausea, diarrhea, abdominal cramps, muscle weakness, hyperreflexia, and Kussmaul’s respirations. Prepare to administer sodium bicarbonate, calcium gluconate, dextrose, insulin, or sodium polystyrene sulfonate.

If the patient has pulmonary disease, check for labored respirations, tachypnea, accessory muscle use, and cyanosis, which are critical signs. Prepare to provide ventilatory support via nasal cannula, mask, or intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Medical Causes

Hepatic encephalopathy. A life-threatening disorder, hepatic encephalopathy initially causes mild personality changes and a slight tremor. The tremor progresses into asterixis — a hallmark of hepatic encephalopathy — and is accompanied by lethargy, aberrant behavior, and apraxia.

Eventually, the patient becomes stuporous and displays hyperventilation. When he slips into a coma, hyperactive reflexes, a positive Babinski’s sign, and fetor hepaticus are characteristic signs. The patient may also experience bradycardia, decreased respirations, and seizures.

Severe respiratory insufficiency. Characterized by life-threatening respiratory acidosis, severe respiratory insufficiency initially produces headache, restlessness, confusion, apprehension, and decreased reflexes. Eventually, the patient becomes somnolent and may demonstrate asterixis before slipping into a coma. Associated signs and symptoms of respiratory insufficiency include difficulty breathing and rapid, shallow respirations. The patient may be hypertensive in early disease but hypotensive later.

Uremic syndrome. A life-threatening disorder, uremic syndrome initially causes lethargy, somnolence, confusion, disorientation, behavior changes, and irritability. Eventually, signs and symptoms appear in diverse body systems. Asterixis is accompanied by stupor, paresthesia, muscle twitching, fasciculations, and footdrop. Other signs and symptoms include polyuria and nocturia followed by oliguria and, then, anuria; elevated blood pressure; signs of heart failure and pericarditis; deep, gasping respirations (Kussmaul’s respirations); anorexia; nausea; vomiting; diarrhea; GI bleeding; weight loss; ammonia breath odor; and metallic taste (dysgeusia).

Other Causes

Drugs. Certain drugs, such as the anticonvulsant phenytoin, may cause asterixis.

Special Considerations

Provide simple comfort measures, such as allowing frequent rest periods to minimize fatigue and elevating the head of the bed to relieve dyspnea and orthopnea. Administer oil baths, and avoid soap to relieve itching caused by jaundice and uremia. Provide emotional support to the patient and his family.

If the patient is intubated or has a decreased LOC, provide enteral or parenteral nutrition. Closely monitor serum and urine glucose levels to evaluate hyperalimentation. Because the patient will probably be on bed rest, reposition him at least once every 2 hours to prevent skin breakdown. Also, recognize that his debilitated state makes him prone to infection. Observe strict hand-washing and aseptic techniques when changing dressings and caring for invasive lines.

Patient Counseling

Explain the underlying disorder, treatment plan, and ways to relieve itching. Teach the patient the importance of planning periods of rest. Discuss measures to reduce the risk of infection with the patient and his family.

Pediatric Pointers

End-stage hepatic, renal, and pulmonary disease may also cause asterixis in children.

REFERENCES

Crawford, A. & Harris, H. (2013). Cirrhosis: A complex cascade of care. Nursing 2014 Critical Care, 8(4), 26–30.

Dijk, J. M., & Tijssen, M. A. (2010). Management of patients with myoclonus: Available therapies and the need for an evidence-based approach. Lancet Neurology, 9, 1028–1036.

Ataxia

Classified as cerebellar or sensory, ataxia refers to incoordination and irregularity of voluntary, purposeful movements. Cerebellar ataxia results from disease of the cerebellum and its pathways to and from the cerebral cortex, brain stem, and spinal cord. It causes gait, trunk, limb, and possibly speech disorders. Sensory ataxia results from impaired position sense (proprioception) due to the interruption of afferent nerve fibers in the peripheral nerves, posterior roots, posterior columns of the spinal cord, or medial lemnisci or, occasionally, caused by a lesion in both parietal lobes. It causes gait disorders. (See Identifying Ataxia.)

Ataxia occurs in acute and chronic forms. Acute ataxia may result from stroke, hemorrhage, or a large tumor in the posterior fossa. With this life-threatening condition, the cerebellum may herniate downward through the foramen magnum behind the cervical spinal cord or upward through the tentorium on the cerebral hemispheres. Herniation may also compress the brain stem. Acute ataxia may also result from drug toxicity or poisoning. Chronic ataxia can be progressive and, at times, can result from acute disease. It can also occur in metabolic and chronic degenerative neurologic disease.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If ataxic movements suddenly develop, examine the patient for signs of increased intracranial pressure and impending herniation. Determine his level of consciousness (LOC), and be alert for pupillary changes, motor weakness or paralysis, neck stiffness or pain, and vomiting. Check his vital signs, especially respirations; abnormal respiratory patterns may quickly lead to respiratory arrest. Elevate the head of the bed. Have emergency resuscitation equipment readily available. Prepare the patient for a computed tomography scan or surgery.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient isn’t in distress, review his history. Ask about multiple sclerosis, diabetes, central nervous system infection, neoplastic disease, previous stroke, and a family history of ataxia. Also, ask about chronic alcohol abuse or prolonged exposure to industrial toxins such as mercury. Find out if the patient’s ataxia developed suddenly or gradually.

If necessary, perform Romberg’s test to help distinguish between cerebellar and sensory ataxia. Instruct the patient to stand with his feet together and his arms at his side. Note his posture and balance, first with his eyes open and then closed. Test results may indicate normal posture and balance (minimal swaying), cerebellar ataxia (swaying and inability to maintain balance with eyes open or closed), or sensory ataxia (increased swaying and inability to maintain balance with eyes closed). Stand close to the patient during this test to prevent his falling.

Identifying Ataxia

CEREBELLAR ATAXIA

With cerebellar ataxia, the patient may stagger or lurch in zigzag fashion, turn with extreme difficulty, and lose his balance when his feet are together.

GAIT ATAXIA

With gait ataxia, the patient’s gait is wide based, unsteady, and irregular.

LIMB ATAXIA

With limb ataxia, the patient loses the ability to gauge distance, speed, and power of movement, resulting in poorly controlled, variable, and inaccurate voluntary movements. He may move too quickly or too slowly, or his movements may break down into component parts, giving him the appearance of a puppet or a robot. Other effects include a coarse, irregular tremor in purposeful movement (but not at rest) and reduced muscle tone.

SENSORY ATAXIA

With sensory ataxia, the patient moves abruptly and stomps or taps his feet. This occurs because he throws his feet forward and outward and then brings them down first on the heels and then on the toes. The patient also fixes his eyes on the ground, watching his steps. However, if he can’t watch them, staggering worsens. When he stands with his feet together, he sways or loses his balance.

SPEECH ATAXIA

Speech ataxia is a form of dysarthria in which the patient typically speaks slowly and stresses usually unstressed words and syllables. Speech content is unaffected.

TRUNCAL ATAXIA

Truncal ataxia is a disturbance in equilibrium in which the patient can’t sit or stand without falling. Also, his head and trunk may bob and sway (titubation). If he can walk, his gait is reeling.

Ataxia may be observed in the patient’s speech, in the movements of his trunk and limbs, or in his gait.

If you test for gait and limb ataxia, be aware that motor weakness may mimic ataxic movements, so check motor strength as well. Gait ataxia may be severe, even when limb ataxia is minimal. With gait ataxia, ask the patient if he tends to fall to one side, or if falling occurs more frequently at night. With truncal ataxia, remember that the patient’s inability to walk or stand, combined with the absence of other signs while he’s lying down, may give the impression of hysteria or drug or alcohol intoxication.

Medical Causes

Cerebellar abscess. Cerebellar abscess commonly causes limb ataxia on the same side as the lesion as well as gait and truncal ataxia. Typically, the initial symptom is a headache localized behind the ear or in the occipital region, followed by oculomotor palsy, fever, vomiting, an altered LOC, and coma.