Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

The location of an abdominal mass provides an important clue to the causative disorder. Here are the disorders most commonly responsible for abdominal masses in each of the four abdominal quadrants.

RIGHT UPPER QUADRANT

Aortic aneurysm (epigastric area)

Cholecystitis or cholelithiasis

Gallbladder, gastric, or hepatic carcinoma

Hepatomegaly

Hernia (incisional or umbilical)

Hydronephrosis

Pancreatic abscess or pseudocysts

Renal cell carcinoma

RIGHT LOWER QUADRANT

Bladder distention (suprapubic area)

Colon cancer

Crohn’s disease

Hernia (incisional or inguinal)

Ovarian cyst (suprapubic area)

Uterine leiomyomas (suprapubic area)

LEFT UPPER QUADRANT

Aortic aneurysm (epigastric area)

Gastric carcinoma (epigastric area)

Hernia (incisional or umbilical)

Hydronephrosis

Pancreatic abscess (epigastric area)

Pancreatic pseudocysts (epigastric area)

Renal cell carcinoma

Splenomegaly

LEFT LOWER QUADRANT

Bladder distention (suprapubic area)

Colon cancer

Diverticulitis

Hernia (incisional or inguinal)

Ovarian cyst (suprapubic area)

Uterine leiomyomas (suprapubic area)

Volvulus

Cholecystitis. Deep palpation below the liver border may reveal a smooth, firm, sausageshaped mass. However, with acute inflammation, the gallbladder is usually too tender to be palpated. Cholecystitis can cause severe right upper quadrant pain that may radiate to the right shoulder, chest, or back; abdominal rigidity and tenderness; fever; pallor; diaphoresis; anorexia; nausea; and vomiting. Recurrent attacks usually occur 1 to 6 hours after meals. Murphy’s sign (inspiratory arrest elicited when the examiner palpates the right upper quadrant as the patient takes a deep breath) is common.

Colon cancer. A right lower quadrant mass may occur with cancer of the right colon, which may also cause occult bleeding with anemia and abdominal aching, pressure, or dull cramps. Associated findings include weakness, fatigue, exertional dyspnea, vertigo, and signs and symptoms of intestinal obstruction, such as obstipation and vomiting.

Occasionally, cancer of the left colon also causes a palpable mass. It usually produces rectal bleeding, intermittent abdominal fullness or cramping, and rectal pressure. The patient may also report fremitus and pelvic discomfort. Later, he develops obstipation; diarrhea; or pencilshaped, grossly bloody, or mucus-streaked stools. Typically, defecation relieves pain.

Crohn’s disease. With Crohn’s disease, tender, sausage-shaped masses are usually palpable in the right lower quadrant and, at times, in the left lower quadrant. Attacks of colicky right lower quadrant pain and diarrhea are common. Associated signs and symptoms include fever, anorexia, weight loss, hyperactive bowel sounds, nausea, abdominal tenderness with guarding, and perirectal, skin, or vaginal fistulas.

Diverticulitis. Most common in the sigmoid colon, diverticulitis may produce a left lower quadrant mass that’s usually tender, firm, and fixed. It also produces intermittent abdominal pain that’s relieved by defecation or passage of flatus. Other findings may include alternating constipation and diarrhea, nausea, a low-grade fever, and a distended and tympanic abdomen.

Gastric cancer. Advanced gastric cancer may produce an epigastric mass. Early findings

include chronic dyspepsia and epigastric discomfort, whereas late findings include weight loss, a feeling of fullness after eating, fatigue and, occasionally, coffee-ground vomitus or melena. Hepatomegaly. Hepatomegaly produces a firm, blunt, irregular mass in the epigastric region or below the right costal margin. Associated signs and symptoms vary with the causative disorder but commonly include ascites, right upper quadrant pain and tenderness, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, leg edema, jaundice, palmar erythema, spider angiomas, gynecomastia, testicular atrophy and, possibly, splenomegaly.

Hernia. The soft and typically tender bulge is usually an effect of prolonged, increased intraabdominal pressure on weakened areas of the abdominal wall. An umbilical hernia is typically located around the umbilicus and an inguinal hernia in either the right or left groin. An incisional hernia can occur anywhere along a previous incision. Hernia may be the only sign until strangulation occurs.

Hydronephrosis. Enlarging one or both kidneys, hydronephrosis produces a smooth, boggy mass in one or both flanks. Other findings vary with the degree of hydronephrosis. The patient may have severe colicky renal pain or dull flank pain that radiates to the groin, vulva, or testes. Hematuria, pyuria, dysuria, alternating oliguria and polyuria, nocturia, accelerated hypertension, nausea, and vomiting may also occur.

Ovarian cyst. A large ovarian cyst may produce a smooth, rounded, fluctuant mass, resembling a distended bladder, in the suprapubic region. Large or multiple cysts may also cause mild pelvic discomfort, low back pain, menstrual irregularities, and hirsutism. A twisted or ruptured cyst may cause abdominal tenderness, distention, and rigidity.

Splenomegaly. The lymphomas, leukemias, hemolytic anemias, and inflammatory diseases are among the many disorders that may cause splenomegaly. Typically, the smooth edge of the enlarged spleen is palpable in the left upper quadrant. Associated signs and symptoms vary with the causative disorder but usually include a feeling of abdominal fullness, left upper quadrant abdominal pain and tenderness, splenic friction rub, splenic bruits, and a low-grade fever.

Uterine leiomyomas (fibroids). If large enough, these common, benign uterine tumors produce a round, multinodular mass in the suprapubic region. The patient’s chief complaint is usually menorrhagia; she may also experience a feeling of heaviness in the abdomen, and pressure on surrounding organs may cause back pain, constipation, and urinary frequency or urgency. Edema and varicosities of the lower extremities may develop. Rapid fibroid growth in perimenopausal or postmenopausal women needs further evaluation.

Special Considerations

Discovery of an abdominal mass commonly causes anxiety. Offer emotional support to the patient and his family as they await the diagnosis. Position the patient comfortably, and administer drugs for pain or anxiety as needed.

If an abdominal mass causes bowel obstruction, watch for indications of peritonitis — abdominal pain and rebound tenderness — and for signs of shock, such as tachycardia and hypotension.

Patient Counseling

Explain any diagnostic tests that are needed, and teach the patient about the cause of the abdominal mass once a diagnosis is made. Explain treatment and potential outcomes.

Pediatric Pointers

Detecting an abdominal mass in an infant can be quite a challenge. However, these tips will make palpation easier for you: Allow an infant to suck on his bottle or pacifier to prevent crying, which causes abdominal rigidity and interferes with palpation. Avoid tickling him because laughter also causes abdominal rigidity. Also, reduce his apprehension by distracting him with cheerful conversation. Rest your hand on his abdomen for a few moments before palpation. If he remains sensitive, place his hand under yours as you palpate. Consider allowing the child to remain on the parent’s or caregiver’s lap. A gentle rectal examination should also be performed.

In neonates, most abdominal masses result from renal disorders, such as polycystic kidney disease or congenital hydronephrosis. In older infants and children, abdominal masses usually are caused by enlarged organs, such as the liver and spleen.

Other common causes include Wilms’ tumor, neuroblastoma, intussusception, volvulus, Hirschsprung’s disease (congenital megacolon), pyloric stenosis, and abdominal abscess.

Geriatric Pointers

Ultrasonography should be used to evaluate a prominent midepigastric mass in thin, elderly patients.

REFERENCES

Dultz, L., Vivar, K ., MacFarland, S., & Hopkins, M. (2011). An abdominal mass with related premenstrual pain. Medscape, June 02, 2011.

Gourgiotis, S., Veloudis, G., Pallas, N., Lagos P., Salemis N. S., & Villias C. (2008). Abdominal wall endometriosis: Report of two cases.

Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology, l49(4), 553–555.

Abdominal Pain

(See Also Abdominal Distention, Abdominal Mass, Abdominal

Rigidity)

Abdominal pain usually results from a GI disorder, but it can be caused by a reproductive, genitourinary (GU), musculoskeletal, or vascular disorder; drug use; or ingestion of toxins. At times, such pain signals life-threatening complications.

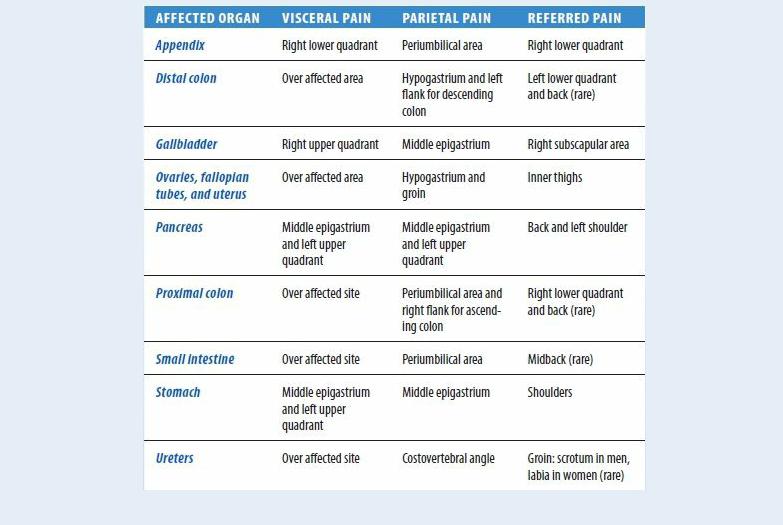

Abdominal pain arises from the abdominopelvic viscera, the parietal peritoneum, or the capsules of the liver, kidney, or spleen. It may be acute or chronic and diffuse or localized. Visceral pain develops slowly into a deep, dull, aching pain that’s poorly localized in the epigastric, periumbilical, or lower midabdominal (hypogastric) region. In contrast, somatic (parietal, peritoneal) pain produces a sharp, more intense, and well-localized discomfort that rapidly follows the insult. Movement or coughing aggravates this pain. (See Abdominal Pain: Types and Locations.)

Abdominal Pain: Types and Locations

Pain may also be referred to the abdomen from another site with the same or similar nerve supply. This sharp, well-localized, referred pain is felt in skin or deeper tissues and may coexist with skin hyperesthesia and muscle hyperalgesia.

Mechanisms that produce abdominal pain include stretching or tension of the gut wall, traction on the peritoneum or mesentery, vigorous intestinal contraction, inflammation, ischemia, and sensory nerve irritation.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient is experiencing sudden and severe abdominal pain, quickly take his vital signs and palpate pulses below the waist. Be alert for signs of hypovolemic shock, such as tachycardia and hypotension. Obtain I.V. access.

Emergency surgery may be required if the patient also has mottled skin below the waist and a pulsating epigastric mass or rebound tenderness and rigidity.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient has no life-threatening signs or symptoms, take his history. Ask him if he has had this type of pain before. Have him describe the pain — for example dull, sharp, stabbing, or burning. Ask if anything relieves the pain or makes it worse. Ask the patient if the pain is constant or intermittent and when the pain began. Constant, steady abdominal pain suggests organ perforation, ischemia, or

inflammation or blood in the peritoneal cavity. Intermittent, cramping abdominal pain suggests that the patient may have obstruction of a hollow organ.

If pain is intermittent, find out the duration of a typical episode. In addition, ask the patient where the pain is located and if it radiates to other areas.

Find out if movement, coughing, exertion, vomiting, eating, elimination, or walking worsens or relieves the pain. The patient may report abdominal pain as indigestion or gas pain, so have him describe it in detail.

Ask the patient about substance abuse and any history of vascular, GI, GU, or reproductive disorders. Ask the female patient about the date of her last period, changes in her menstrual pattern, or dyspareunia.

Ask the patient about appetite changes. Ask about the onset and frequency of nausea or vomiting. Find out about increased flatulence, constipation, diarrhea, and changes in stool consistency. When was the last bowel movement? Ask about urinary frequency, urgency, or pain. Is the urine cloudy or pink?

Perform a physical examination. Take the patient’s vital signs, and assess skin turgor and mucous membranes. Inspect his abdomen for distention or visible peristaltic waves and, if indicated, measure his abdominal girth.

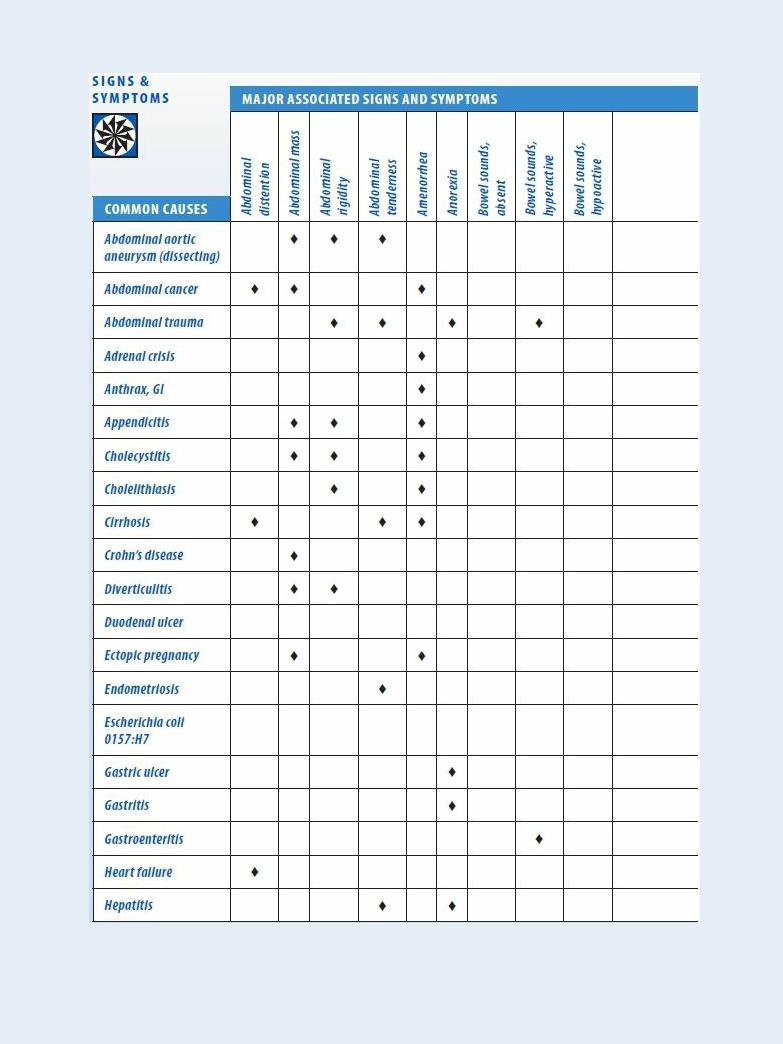

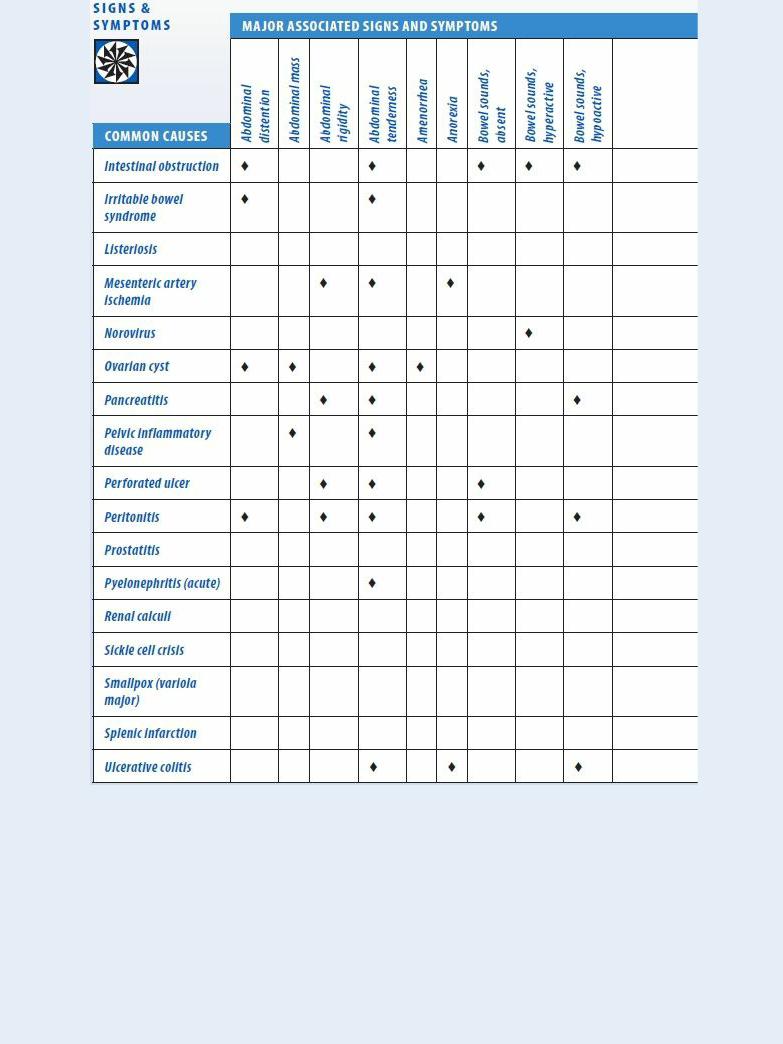

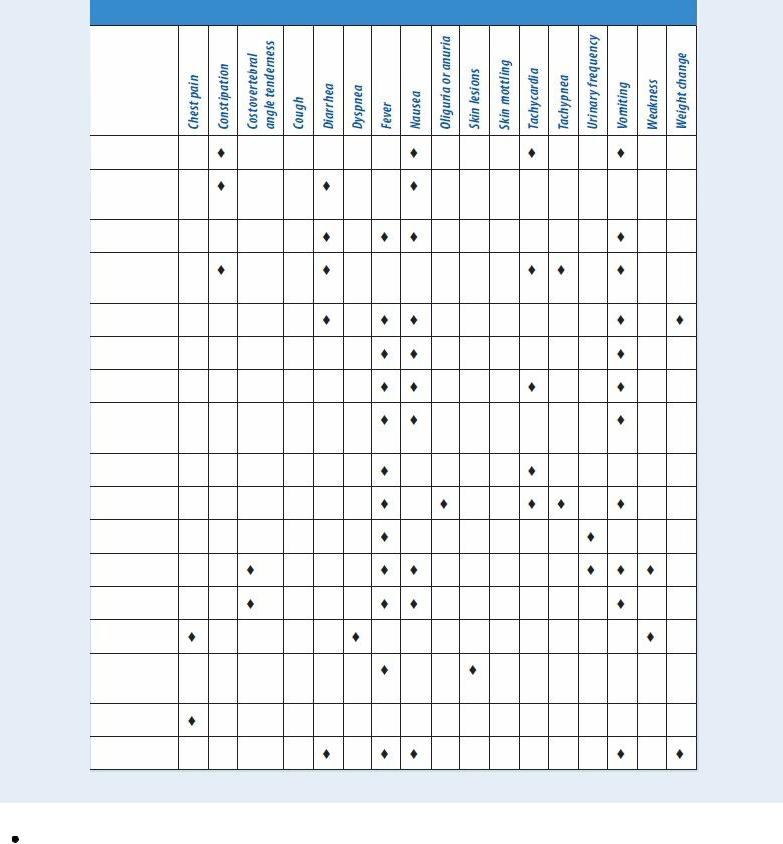

Auscultate for bowel sounds, and characterize their motility. Percuss all quadrants, noting the percussion sounds. Palpate the entire abdomen for masses, rigidity, and tenderness. Check for costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness, abdominal tenderness with guarding, and rebound tenderness. (See Abdominal Pain: Common Causes and Associated Findings, pages 16 to 19.)

Medical Causes

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (dissecting). Initially, this life-threatening disorder may produce dull lower abdominal, lower back, or severe chest pain. Usually, abdominal aortic aneurysm produces constant upper abdominal pain, which may worsen when the patient lies down and may abate when he leans forward or sits up. Palpation may reveal an epigastric mass that pulsates before rupture but not after it.

Other findings may include mottled skin below the waist, absent femoral and pedal pulses, lower blood pressure in the legs than in the arms, mild to moderate abdominal tenderness with guarding, and abdominal rigidity. Signs of shock, such as tachycardia and tachypnea, may appear.

Abdominal cancer. Abdominal pain usually occurs late in abdominal cancer. It may be accompanied by anorexia, weight loss, weakness, depression, and abdominal mass and distention.

Abdominal trauma. Generalized or localized abdominal pain occurs with ecchymoses on the abdomen, abdominal tenderness, vomiting and, with hemorrhage into the peritoneal cavity, abdominal rigidity. Bowel sounds are decreased or absent. The patient may have signs of hypovolemic shock, such as hypotension and a rapid, thready pulse.

Adrenal crisis. Severe abdominal pain appears early, along with nausea, vomiting, dehydration, profound weakness, anorexia, and fever. Later signs are progressive loss of consciousness; hypotension; tachycardia; oliguria; cool, clammy skin; and increased motor activity, which may progress to delirium or seizures.

Abdominal Pain: Common Causes and Associated Findings

Anthrax, GI. An acute infectious disease, GI anthrax is caused by the gram-positive, sporeforming bacterium Bacillus anthracis. Although the disease most commonly occurs in wild and domestic grazing animals, such as cattle, sheep, and goats, the spores can live in the soil for many years. The disease can occur in humans exposed to infected animals, tissue from infected animals, or biological warfare. Most natural cases occur in agricultural regions worldwide. Anthrax may occur in any of the following forms: cutaneous, inhaled, or GI.

GI anthrax is caused by eating contaminated meat from an infected animal. Initial signs and symptoms include loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and fever. Late signs and symptoms include abdominal pain, severe bloody diarrhea, and hematemesis.