Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Advanced Imaging of the Abdomen - Jovitas Skucas

.pdf

205

COLON AND RECTUM

question. Some gas-containing abscesses mimic bowel loops. Ultrasonography identifies some noninflamed diverticula, with these diverticula often containing echogenic material. Ultrasonography findings of diverticulitis include bowel wall thickening, seen as a thick hypoechoic layer, and pericolonic fat inflammation, seen as a hyperechoic layer. The suspect diverticulum, if identified, appears as a hyperechoic focus adjacent but outside the colonic lumen. A flask-like or arrowhead-like hypoechoic appearance is occasionally detected in colon segments affected by diverticulitis. Fistulas have a linear, hypoechoic appearance.

Overlying intestinal gas is avoided with endorectal US. Occasionally a perforation, abscess, or fistula not shown on transabdominal US is identified with endorectal US.

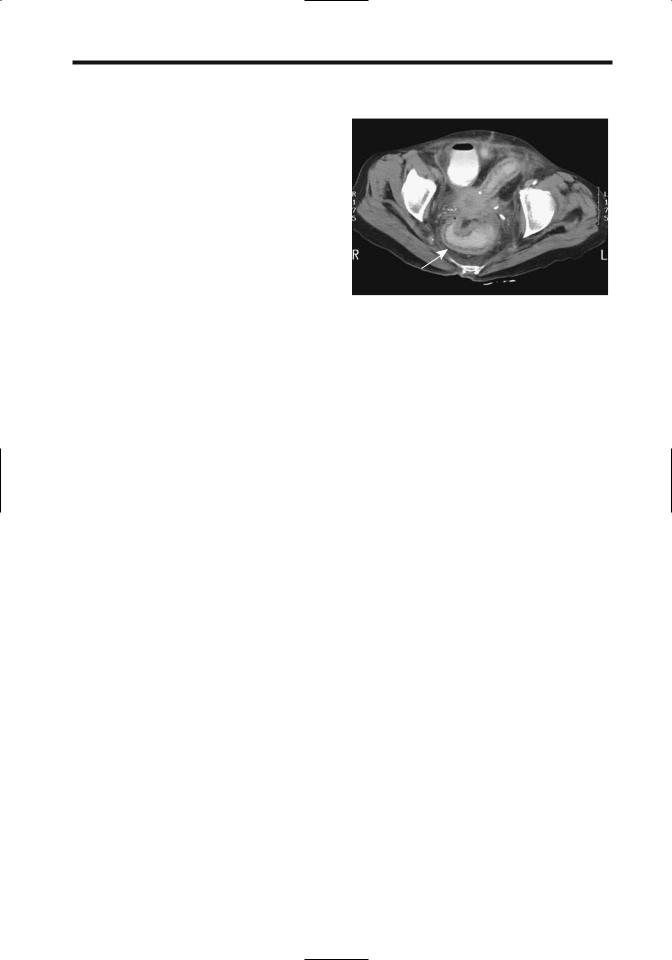

Bowel wall thickening, abscesses, fistulas, and sinus tracts are well detected with MRI (Fig. 5.8). Surrounding inflammation appears on T1-weighted images as hypointense stranding within hyperintense fat. The inflammatory com-

ponent enhances postcontrast. As with CT, a necrotic colon cancer is difficult to distinguish from diverticulitis with MR.

In differentiating right-sided colonic diverticulitis from a carcinoma, detection of an inflamed diverticulum by CT had a mean sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 93%, while preserved wall contrast enhancement had a mean sensitivity and specificity of 90% and 95%, respectively (64). Follow-up US in patients believed to suffer from acute right colonic diverticulitis reveals spontaneous evacuation of the inflamed diverticular content into the colonic lumen.

Complications

Complications of diverticulitis include fistula, abscess, perforation with peritonitis, and obstruction. The latter complication involves either colon or an adjacent loop of small bowel.

Among patients with diverticular fistulas, slightly less than half are colovesical, similar

B

A

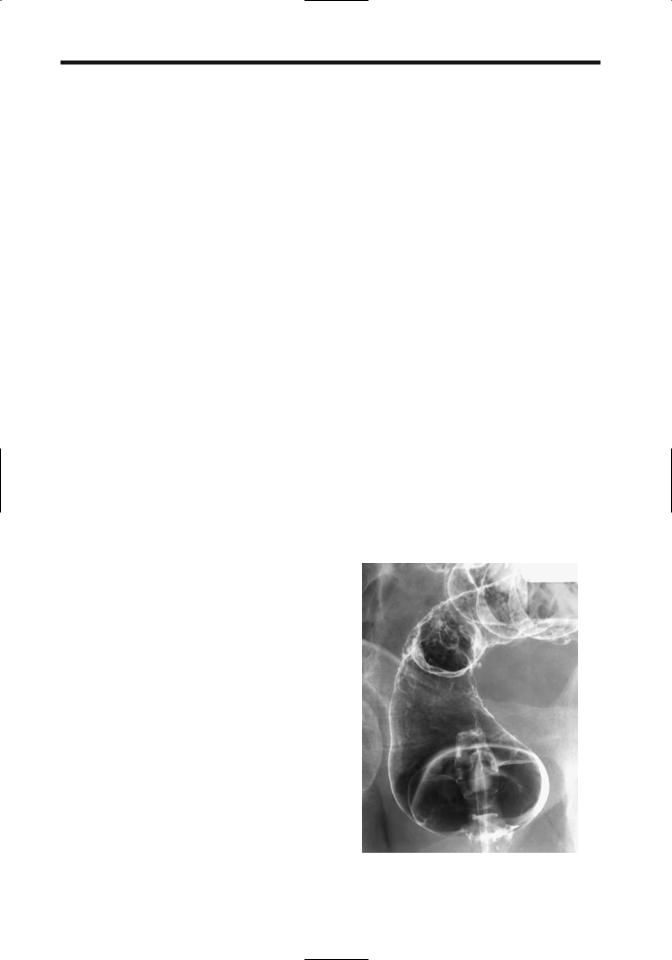

Figure 5.8. CT (A) and MR (B,C) colonography of diverticulitis. |

|

Axial CT is commonly used with suspected diverticulitis but |

|

value of MR is not yet established. (Courtesy of Wolfgang |

|

Luboldt, M.D., Johann Wolfgang Goethe University, Frankfurt- |

|

am-Main.) |

C |

206

number are colovaginal and a few percent are colocutaneous and coloenteric. Rare colouterine and colosalpingeal fistulas have been reported. A rare fistula extends into the thigh and presents either as a septic arthritis or as subcutaneous emphysema. A rare complication of sigmoid diverticulitis is vertebral osteomyelitis. Most fistulas are readily detected by CT. In fact, CT is superior to cystoscopy in detecting colovesical fistulas.

Inferior mesenteric vein thrombophlebitis is an underappreciated complication of sigmoid diverticulitis; CT reveals an enlarged and inflamed inferior mesenteric vein. At times gas is identified within the vein lumen. Sigmoid diverticulitis is a common cause of multiple liver abscesses and portal venous gas.

On an acute basis, bowel obstruction is due to inflammation and edema. Small bowel obstruction develops if a loop of small bowel becomes adherent at the site of inflammation or abscess. A persisting obstruction implies a fibrotic stricture and is an indication for resection. A barium enema can generally differentiate between a benign diverticular stricture and one due to cancer. A correct barium enema differentiation between benign and malignant strictures was made in most patients with a documented sigmoid strictures (65); only one benign stricture was called malignant, but caution was advised for benign-appearing strictures; nine malignant strictures were called benign.

Therapy

In general, a first episode of uncomplicated diverticulitis is managed conservatively. Most patients with a typical acute episode treated medically with bowel rest and antibiotics do not undergo surgery. Surgery is considered in those with recurrent attacks or those unresponsive to conservative therapy.

Chronic diverticulitis has been treated laparoscopically. Similar to other laparoscopic procedures, patients have a faster recovery and shorter hospital stay than those undergoing conventional surgery. The procedure costs more than an open resection in the United States because of longer operating room time, but the reverse applies in Germany.

Perforated sigmoid diverticulitis is generally resected, a colostomy performed, and a

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

Hartmann’s pouch or mucus fistula created, followed later by a second laparotomy to reestablish colon continuity. One option feasible in some patients is initial percutaneous abscess drainage, followed in a week or so by resection and primary anastomosis, thus sparing the patient a temporary colostomy and a second laparotomy.

Surprisingly, some surgically treated patients continue being symptomatic.

Infective Colitis

Mentioned here are only those infections primarily affecting the large bowel; others are covered in Chapter 4. Patients with salmonella, shigella, or yersinia infection develop bowel wall thickening, a nonspecific finding. Yersinia infection also leads to adenopathy and focal ulcerations of involved bowel (Fig. 5.9).

In patients with acute infectious diarrhea and a single identified enteropathogen, a majority are due to invasive pathogens; the presence of blood in stool is almost pathognomonic for an invasive agent but this finding has a low sensitivity.

Figure 5.9. Yersinia enterocolitis. A barium enema reveals ulcers scattered throughout the rectum.

207

COLON AND RECTUM

Escherichia coli

Enterohemorrhagic colitis is caused by a noninvasive E. coli serotype, often manifesting in outbreaks due to undercooked food. The contiguous right colon tends to be predominantly involved, with imaging findings mimicking either mild-to-moderate ischemic colitis or Crohn’s disease. Computed tomography appears to be more sensitive than conventional radiographs in identifying diseased segments (66).

Hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with E. coli infection has an intestinal prodromal phase, with a hemorrhagic acute colitis found in some patients. In fact, in North America, hemolytic-uremic syndrome after E. coli hemorrhagic colitis is the main cause of pediatric renal failure requiring kidney transplant. During this prodrome phase color Doppler US reveals a thickened, markedly avascular colonic wall.

Phlegmonous Colitis

Phlegmonous colitis is an often unrecognized and usually fatal condition caused by bacterial infection. In an autopsy study of patients with phlegmonous colitis, all had either underlying hepatic cirrhosis or subacute liver atrophy believed to be due to viral hepatitis (67); phlegmonous colitis was not suspected prior to death. Pathologic findings consisted of cecal involvement (77%), edema and submucosal phlegmonous changes (100%), bacterial infection (100%), no detectable mucosal injury (92%), and acute peritonitis (15%).

At times total colectomy is necessary for adequate disease control.

Amebic Colitis

Amebiasis, or infection by Entamoeba histolytica, ranges from asymptomatic carriers to a fulminant and necrotizing colitis. At times during an acute phase the clinical presentation suggests inflammatory bowel disease, with severe intestinal bleeding, progression to fulminant colitis, or even perforation. Colonic mucosal necrosis is common.

Among patients with fulminant amebic colitis seen at a referral center in Mexico, about half also had a coexistent amebic liver abscess (68). The reverse is also true; in 45 patients with amebic liver abscesses, colonoscopy revealed

colonic involvement in 58% (69). Most often acute colonic involvement consists of discrete ulcers in the right colon. Coloenteric or rectovaginal fistulas are not common with intestinal amebiasis.

Tuberculous colitis and chronic amebic colitis tend to have a similar imaging appearance, although tuberculosis is more prone to involve mesentery and small bowel (Fig. 5.10).

Schistosomiasis

Schistosoma mansoni, or intestinal bilharziasis, is endemic in West Central Africa, the Arabian peninsula, some Caribbean islands, and the Atlantic Ocean side of South America. Chronic infection tends to localize mostly in mesenteric veins draining the colon; eggs are deposited in submucosal veins and pass into the bowel lumen. Associated portal hypertension, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly develop eventually. Gastrointestinal bleeding in infected individuals is from two sources: either direct colonic infestation or bleeding esophageal varices secondary to portal hypertension.

Schistosoma japonicum has been eradicated in Japan, and currently is found in China, Thailand, Philippines and Indonesia; Schisto-

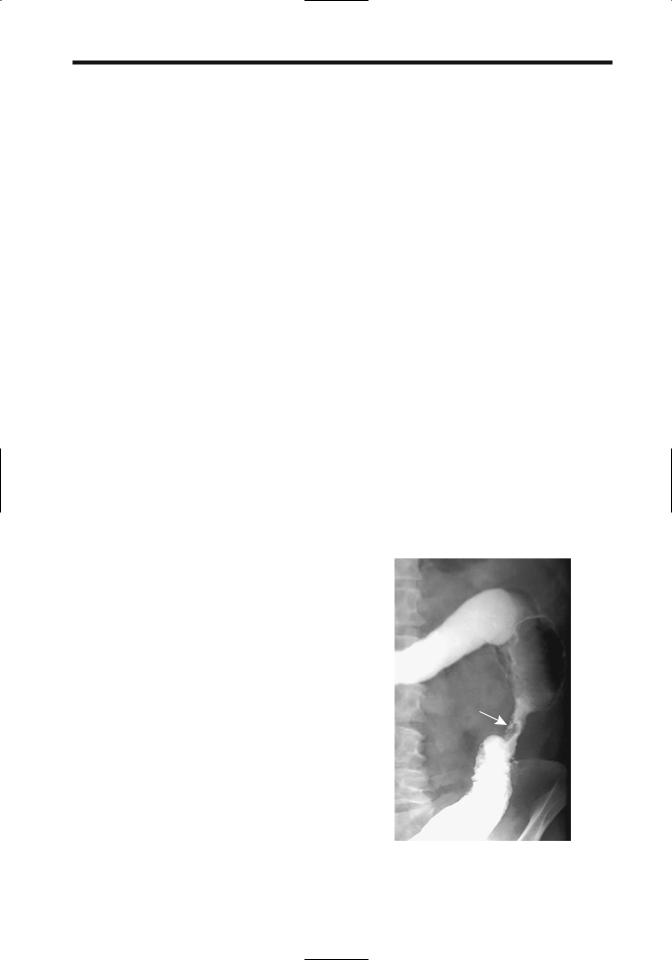

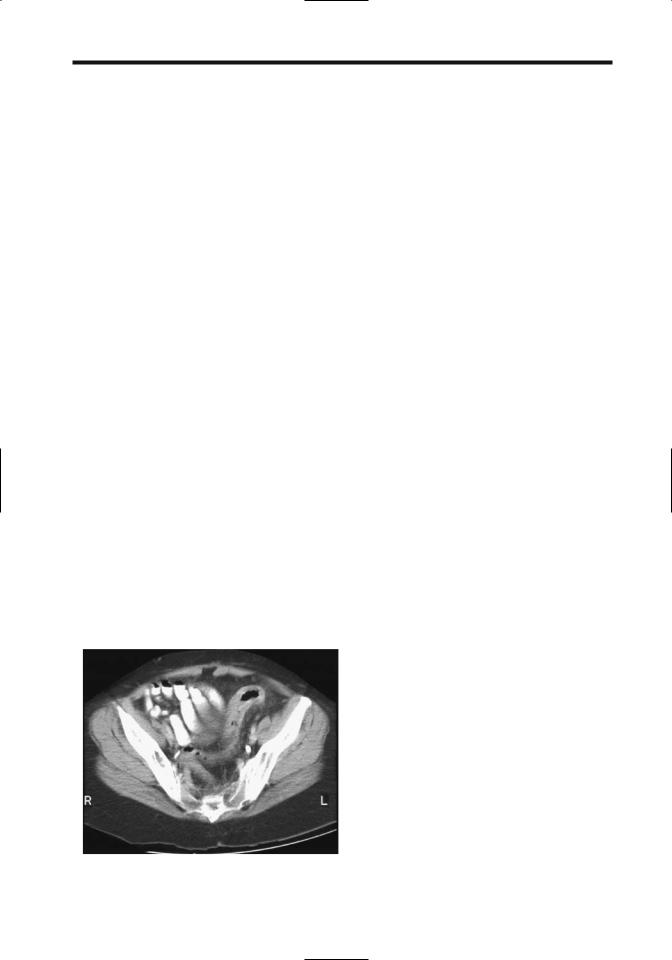

Figure 5.10. Descending colon stricture secondary to amebic colitis (arrow). A tuberculous stricture or one due to inflammatory bowel disease can have a similar appearance.

208

soma mekongi is mostly in the Mekong valley; these have a similar bowel presentation and are a major cause of liver fibrosis and resultant portal hypertension. Schistosoma intercalatum, endemic in central Africa, affects the rectosigmoid and manifests with pain, diarrhea, and rectal bleeding.

Colonic ulcers, neovascularity, fibrosis, and giant cell granulomas surround S. mansoni eggs. Hyperemia and telangiectasia are the endoscopic findings of colonic infestation, indicative of increased vascularity, changes also secondary to portal hypertension developing in some patients with schistosomal liver involvement. Such portal colopathy is not pathognomonic for this condition but is also found in patients with portal hypertension due to other causes.A granuloma can mimic an adenomatous polyp during colonoscopy.

Computed tomography reveals a thickened, poorly marginated bowel wall having varying contrast enhancement. These findings presumably reflect underlying inflammation and portal hypertension.

Tuberculosis

Abdominal tuberculosis is discussed in more detail in Chapter 14.

In endemic areas, about 10% of gastrointestinal tuberculosis involves the colorectum and consists of strictures, colitis and, least common, polyps (70). Symptoms tend to be those of chronic infection.A majority of intestinal tuberculosis is secondary to pulmonary involvement.

Biopsies often fail to establish a diagnosis, at times revealing granulomas, although nonspecific inflammation is a more common histologic finding. Resected specimens reveal inflammation, caseating granulomas, and Langhans giant cells, all consistent with tuberculosis, but acid-fast bacilli are rarely isolated.

A not atypical clinical history consists of constipation, weight loss, and abdominal pain, with occasional rectal bleeding. Blood tests and chest radiographs are often noncontributory. Massive rectal bleeding is uncommon.

In its chronic form tuberculosis results in colonic strictures, ileocecal valve deformity, ulcerations, polyps, and fibrous bands, with the right colon and ileum being most often involved. The cecal lumen narrows. A wide, gaping ileocecal valve, often with deformed and

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

thickened valve lips, is a characteristic finding but not always present. The terminal ileum is deformed, narrowed and suggests Crohn’s disease. Colonic involvement tends to be segmental, at times involving multiple sites. A tuberculous stricture often mimics a benignappearing colonic stricture such as is seen in Crohn’s disease (Fig. 5.11). Rarely, colonic tuberculosis manifests as a diffuse pancolitis.

Colonic tuberculosis does lead to fistulas, including an occasional duodenocolic fistula, but fistulas and sinus tracts are less common than with Crohn’s disease.

Tuberculous rectal involvement is uncommon. A barium enema in these patients reveals a stricture of variable length, deep ulcerations, and a widened presacral space; biopsy simply yields a granulomatous infiltrate. Anal and perianal tuberculosis results in findings similar to Crohn’s disease.

Over the years a number of reports described cecal tuberculosis coexisting with a cecal adenocarcinoma. Due to the distortion, even at surgery an underlying carcinoma can be difficult to identify.

These patients respond to antitubercular therapy and often do not require surgery.

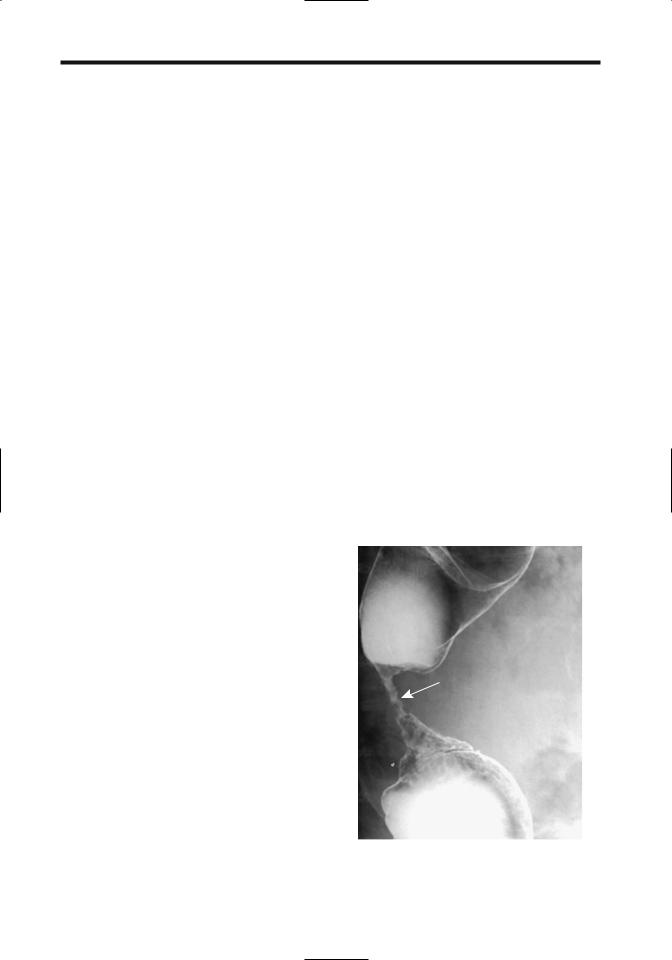

Figure 5.11. Tuberculous colitis presenting as a stricture (arrow). An ameboma, ischemic stricture, or even inflammatory bowel disease can have a similar appearance.

209

COLON AND RECTUM

A double-contrast barium enema reveals skip lesions and multiple, transverse, or circumferential ulcers, with the ulcers ranging from shallow to deep and having an uneven, nodular margin. Inflammatory polyps are common, occasionally mimicked a malignancy.

Actinomycosis

Actinomyces israelii, an anaerobic bacterium, is normally found in the upper gastrointestinal tract and here it rarely causes disease. In the pelvis, on the other hand, actinomycosis results in fistulas, inflammatory tumors, strictures, and abscesses. It causes more harm in women and is often associated with intrauterine devices. The diagnosis is often established by culture of a removed contraceptive device.

With colonic involvement, generally rectosigmoid, the induced marked fibrosis tends to mimic a colon cancer by barium enema, CT, and endoscopy, except that a common hallmark of actinomycosis is extensive fistulization, at times even cutaneously, an uncommon finding with a cancer. Thus a barium enema often reveals extensive fistulas, generally more than is seen with diverticulitis or even Crohn’s disease. Computed tomography shows a contrast-enhancing tumor, often containing a cystic component. Ileocecal region involvement leads to ileocecal valve enlargement.

Computed tomography of abdominopelvic actinomycosis reveals concentric or eccentric bowel wall thickening of varying contrast enhancement, together with a heterogeneously enhancing tumor adjacent to involved bowel (71). At times an abscess is in the differential diagnosis. Progression over time tends to be gradual, raising further suspicion for cancer. As one example, a barium enema in a patient revealed a tumor at the base of the cecum and a narrowed sigmoid colon, whereas CT identified a mass in the ileocecal region (72); 7 months later adjacent tissues were more infiltrated, the cecum more involved, the sigmoid colon further narrowed, and pelvic extension identified. A pelvic abscess and appendiceal carcinoma were in the differential diagnosis. Laparotomy and histology revealed chronic inflammation involving the ileocecal region, right ureter, fallopian tube, ovary, bladder, psoas muscle, and abdominal wall, and confirmed the underlying actino-

mycosis. At times aspiration from an infected mass provides the diagnosis.

Even with extensive involvement, once a diagnosis of actinomycosis is established medical therapy rather than resection is generally warranted. In practice, however, the diagnosis is difficult, and some patients are noncompliant with long-term antibiotic therapy.

Anisakiasis

Anisakiasis is considerably more common in the upper gastrointestinal tract than in the colon. Several patients with ascending colon involvement by Anisakis simplex larvae presented with an acute abdomen. Imaging identifies focal colonic wall thickening, mimicking diverticulitis or ischemia.

Viral

Herpes simplex colitis leads to aphthae and erosions. Quite often only a short colonic segment is involved.

Cytomegalovirus colitis is rare in immunocompetent patients. Infection has led to fulminant hemorrhagic colitis. Imaging reveals colonic wall thickening and ulceration, in some patients mimicking a neutropenic colitis (Fig. 5.12).

A rare immunocompetent patient develops primary cytomegalovirus colitis, followed by ulcerative colitis, raising the possibility of cytomegalovirus infection triggering the onset of ulcerative colitis.

Typhlitis/Neutropenic Colitis

Typhlitis is not a specific disease but a descriptive term of cecal inflammation. The term was more in vogue at the beginning of the 20th century, prior to appendicitis being identified as a separate entity. Currently the term typhlitis is reserved mostly for a primarily neutropenic cecal infiltration developing in a setting of acute leukemia, lymphoma, aplastic anemia, and other immunologic deficiency conditions.

Neutropenic colitis is common in immunocompromised neutropenia patients, most often in patients with hematologic malignancies, transplant patients, and those with AIDS. A viral organism is isolated in some, with cytomegalovirus predominating. Superimposed

210

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

A

B

B

Figure 5.12. Cytomegalovirus colitis. A,B: Two pelvic CT images reveal a dilated, thick-walled colon (arrows). Pseudomembranous colitis is in the differential diagnosis. (Courtesy of Patrick Fultz, M.D., University of Rochester.)

focal ischemia and infection result in bowel wall inflammation and, if severe enough, necrosis. The differential diagnosis often includes primary infection and neoplastic infiltration.

Imaging reveals cecal wall thickening extending for varying lengths into the ascending colon. Lumen distention is an inconsistent finding. Often CT detects a hypodense cecal wall due to edema. Surrounding inflammation, fat stranding, and pericolonic fluid are common.

Drug-Related Colitis

Classification of some of the following conditions is arbitrary. Ischemia is often the final end point.

Antibiotic-Associated

(Pseudomembranous) Colitis

Clinical

Whether the term antibiotic-associated colitis or pseudomembranous colitis is used is a personal choice; some authors simply label this condition Clostridium difficile diarrhea. A pseudomembrane is not always identified; then again, an occasional adult develops pseudomembranous colitis, even a fulminant one, without recent antibiotic therapy. A similar condition was already recognized in the preantibiotic era when it was encountered mostly after surgery and manifested as an enteritis. Associated mal-

nutrition, immunodeficiency, and colonic stasis, especially in fragile elderly patients, result in high morbidity and mortality.

Numerous antibiotics and other drugs are responsible for this condition. Antitumoral agents induce a pseudomembranous colitis, presumably due to their combination antimitotic and antibacterial activity. 5-Fluorouracil often results in a mild, nonspecific colitis but rarely leads to florid pseudomembranous colitis. Interferon occasionally results in an acute colitis similar to inflammatory bowel disease. Toxinproducing strains of the anaerobic bacterium C. difficile are implicated in almost all instances, although rarely Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium perfringens, Yersinia enterocolitica, and some strains of salmonella and shigella are involved. Rarely, more than one organism is involved.

Pathogenesis consists of the replacement of normal colonic bacterial flora by C. difficile with release of mucosal toxins. Damage is secondary to at least two toxins: an enterotoxin (toxin A), which induces intestinal tissue damage and fluid response, and a cytotoxin (toxin B), which produces an in vivo additive effect. A fast and inexpensive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test for the enterotoxin is available, although it is not foolproof. Also, an antibody response to these toxins is detected in some asymptomatic carriers.

Complicating the picture is a wide spectrum of clinical presentations ranging from an asymptomatic carrier to a fulminant, life-threatening

211

COLON AND RECTUM

toxic megacolon-like condition. Findings are most evident in the colon, although more extensive bowel involvement develops in some patients. Clinically, colitis with fever, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and elevated white cell count are common.

An experienced observer can suggest the diagnosis during sigmoidoscopy. Biopsy of characteristic plaques confirms the diagnosis. One should avoid making a diagnosis of antibiotic-associated colitis based solely on stool culture for C. difficile; asymptomatic carriers exist both in adults and neonates, especially in hospitals.

In spite of adequate medical management, some patients progress to toxic megacolon and perforation. Occasionally a colectomy is necessary. One novel therapy is formation of a colostomy and instillation of vancomycin through the colostomy.

Imaging

Conventional radiographs detect only more extreme bowel involvement. A toxic megacolon appearance is indistinguishable from that seen in inflammatory bowel disease.

A barium enema is not necessary and is poorly tolerated by these patients. Performed early in the course of this condition it shows multiple small plaques, a shaggy bowel wall outline, thickened haustra, and bowel wall thickening.

Ascites develops as the condition progresses. Ascites is also found in a number of other colitides (except ulcerative colitis), and its presence does not aid in narrowing a differential diagnosis.

Once pseudomembranous colitis is well established, CT detects nodular haustral thickening, thickened colonic wall ranging from segmental to a pancolitis, ascites, and pericolonic edema (Fig. 5.13); the markedly serrated lumen identified by conventional radiography has been called the CT accordion sign. These serrations should not be confused with deep ulcers or sinus tracts. One should keep in mind, however, that the accordion sign is not specific for pseudomembranous colitis and other causes of colonic inflammation or edema also result in this sign.

Arterial phase CT reveals a target sign, consisting of a hyperdense inner and outer wall

Figure 5.13. Clostridium difficile colitis. CT reveals circumferential colonic and rectal wall thicken (arrow). (Courtesy of Patrick Fultz, M.D., University of Rochester.)

margin with an interposed hypodense submucosa. A number of disorders have a similar abnormal appearance. Although CT can suggest the diagnosis in the appropriate clinical setting, laboratory findings are more sensitive. At one institution, C. difficile colitis was explicitly diagnosed at CT with a 52% sensitivity and 93% specificity (73).

Ultrasonography shows a thickened bowel wall and luminal narrowing. Some patients have two concentric bowel wall rings: a thick heterogeneous hyperechoic inner ring composed of plaques and mucosal and submucosal edema, and a thinner hypoechoic outer ring representing muscularis propria.

Indium-111–labeled leukocyte imaging identifies bowel activity. 18F-FDG-PET in a patient with C. difficile colitis can result in marked 18F-FDG uptake throughout the colon wall.

Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory

Drug Colopathy

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs are associated with a nonspecific colitis. Analgesic suppositories cause extensive proctitis, including ulcerations. They have been implicated in collagenous colitis. They also exacerbate a preexisting colitis. Pathogenesis of this condition is unclear, although vascular stenoses and resultant ischemic are likely causes.

These drugs are implicated in erosions and colonic ulcers. An occasional patient develops a

212

benign-appearing colonic stricture, including short, diaphragm-like colonic strictures (74). Biopsy reveals cryptitis, fibrosis, and granulomas, suggesting Crohn’s disease, but the findings clear after drug discontinuation. Colitis recurs with drug rechallenge.

Bloody diarrhea and abdominal pain are typical presentations and, on a more chronic basis, weight loss and iron-deficiency anemia ensue.

Cathartic Colitis

Cathartic colitis is a term applied to the colonic findings developing secondary to chronic stimulant laxative abuse. Often implicated is chronic ingestion of bisacodyl, phenolphthalein, senna, and casanthranol. Anthranoid laxatives such as senna (Cassia senna) and cascara (Rhamnus purshiana) are commonly used purgatives in treating constipation. After passing unabsorbed to the colon, they are metabolized to active aglycones, which act as laxatives by damaging epithelial cells, thus affecting normal absorption, secretion, and bowel motility. Damaged epithelial cells eventually produce a pigmented mucosal, called (pseudo)melanosis coli. This pigmentation gradually disappears after drug cessation. When detected endoscopically, melanosis coli usually implies chronic anthranoid laxative abuse, although melanosis coli has also been described in patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease (75).

Previous studies suggested that anthranoid laxative use and resultant melanosis coli is tumorigenic, and these patients are at increased risk for colorectal cancer, but a more recent prospective study found no significant risk for either colorectal adenomas or carcinomas (76).

Colonic redundancy and dilation are common in patients with chronic constipation, but loss of haustral folds is found only in those taking laxatives.

Cocaine Colitis

Cocaine colitis is considered a form of ischemic colitis. Left colon lesions predominate and consist of ulcers, hemorrhagic, edematous mucosa, and inflammatory polyps; rectal involvement is common, an unusual finding with classic ischemic colitis. Histologically, lesions range from acute to chronic, probably

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

reflecting repeated cocaine use. When severe, patchy necrosis to the point of perforation and multiple small vessel thrombi develop.

Collagenous/Microscopic/Lymphocytic Colitis

Collagenous colitis and microscopic colitis (also called lymphocytic colitis) are recently recognized clinicopathologic conditions, but whether these are separate entities or variations of a single condition is not clear. Little evidence supports two distinct disorders; the immune abnormalities are similar in both and a similar immune mechanism appears involved. The two names reflect their histologic findings. Pathogenesis of both appears to be either inflammatory or autoimmune in nature; a role for infection or drug toxins is speculative.

Collagenous/lymphocytic colitis is most often associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Underlying rheumatologic and autoimmune diseases are often present; even celiac disease exists in some patients. Some patients have associated gastric and duodenal subepithelial collagenous deposits or Crosby capsule biopsy evident but subclinical small intestinal abnormalities. A possible pathogenetic association between interstitial cystitis and collagenous colitis has been raised. This condition may not be limited to the colon.

Biopsies in both collagenous and lymphocytic colitis reveal intraepithelial lymphocytes, probably a reflection of epithelial injury, and a lamina propria plasma cell and neutrophil infiltrate. In collagenous colitis a thickened collagen band is evident beneath the surface epithelium, a finding missing in microscopic colitis. In an occasional patient microscopic colitis progresses to collagenous colitis.

Symptoms in patients with collagenous colitis tend to be nonspecific, with chronic watery diarrhea and abdominal pain predominating. Most patients are women in their sixth decade or older. Most patients have spontaneous or treatment-related resolution of their symptoms. One unusual association was salmonella osteomyelitis developing in a patient with collagenous colitis (77).

A barium enema or endoscopy reveals no specific abnormality in most patients. In a minority macroscopic erosions and even ulcerations are evident. Endoscopic findings also

213

COLON AND RECTUM

include edema, erythema, and an abnormal vascular pattern (78). The diagnosis rests on histopathologic findings.

images, and enhanced slightly after gadolinium (79); the authors postulated that intracytoplasmic siderocalcific inclusions accounted for the CT and MRI findings.

Diversion Colitis

After surgical bowel diversion and formation of an excluded segment, some patients develop inflammatory changes in the diverted bowel. These consist of aphthae, crypt abscesses, and easy friability. Large ulcerations develop in an occasional patient.

Malacoplakia

Colonic malacoplakia is rare, occurring both in isolation and in association with other diseases. Although not a neoplasm, malacoplakia is locally aggressive and invades surrounding tissues. At times it is multifocal. Kidney transplant patients, in particular, appear prone to develop colorectal malacoplakia; in some, malacoplakia appears related to immunosuppression therapy. It has developed in a colon adenoma, although more often it is associated with a carcinoma, where malacoplakia is located adjacent to the tumor.

Rare clinical manifestations of malacoplakia include massive hemorrhage and cecal perforation.

Imaging usually suggests a malignancy. Some develop multiple polyps. Malacoplakia in one patient was hyperdense on unenhanced CT, hypointense both on T1and T2-weighted MR

Other Colitides

A barium enema should be diagnostic of colitis cystica profunda. If large enough, the fluid-filled cysts are also visible with CT or endorectal US (if the rectum is involved).

Occasional reports describe a hot-water enema or some chemical inducing colitis (Fig. 5.14).

Xanthogranulomatous inflammation of the sigmoid colon has led to colonic obstruction.

Kawasaki disease (mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome) in a child can present with fever and focal colitis.

Neonatal Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Clinical

A disease more common in premature neonates, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) typically starts with bloody diarrhea or distention several days after birth. Although a number of factors have been postulated, epidemic outbreaks in newborn nurseries implicate an infectious role. The final common pathway is probably ischemia with subsequent mucosal or more severe damage. A condition similar to neonatal NEC occasionally develops in older infants. Many

A  B

B

Figure 5.14. Chemical-induced colitis in a patient who was giving herself hydrogen peroxide enemas for constipation. A,B: CT shows marked rectosigmoid wall thickening (arrows). (Courtesy of Thomas Miller, M.D., San Luis Obispo, California.)

214

have had prior major surgery, and underlying ischemia appears to be a factor.

Necrotizing enterocolitis carries a high mortality, averaging 50% in some centers, with mortality varying inversely with gestational age and birth weight. Extensive bowel resection may result in a short gut syndrome.

Imaging

Any part of the bowel can be involved, although the most common sites are distal small bowel and proximal colon. Involvement ranges from diffuse to segmental. Among neonates undergoing surgery, about a third have NEC totalis (80). Strictures,usually colonic,and more often in the left colon, develop as a late complication.

Conventional radiography early in the course of NEC reveals small bowel dilation, then colonic distention. In some neonates focal regions of bowel lumen narrowing and wall thickening are evident, nonspecific findings. Eventually pneumatosis intestinalis and portal venous gas develop in some, findings almost pathognomonic for NEC in neonates (it is a gas and not air as some of the literature claims). Although in adults portal venous gas carries a grave connotation, in these neonates such gas represents a more benign finding. Complicating the picture, some babies even with severe NEC do not develop pneumatosis or portal venous gas. Ascites is usually a sign of severe NEC, a finding difficult to detect with conventional radiography but readily apparent with US. Although these findings are useful as a guide, they are insensitive in predicting impending perforation.

In neonates with NEC and portal venous gas, venous gas developed within 24 hours of onset of abdominal distention, feeding intolerance, or a finding of rectal blood (80); pneumatosis intestinalis was identified in 80%, and 20% progressed to perforation. Venous gas initially was transient but recurred in some of these neonates.

Urine CT attenuation is increased after enteral iohexol in neonates with NEC; in normal neonates urine CT attenuation is slightly above water. A serial increase in urine CT attenuation coefficients after oral ingestion of iohexol is associated with clinical deterioration (81).

Complications of NEC include perforation, often early in the course. Serial conventional

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

horizontal-beam radiographs are necessary to detect a subtle perforation. Perforation, or impending perforation, is an indication for surgery.

A contrast enema is usually not performed during the acute episode because of a perceived increased risk of perforation. Most strictures are detected with a barium enema later, after the acute insult has resolved. An occasional sequela is an enteroenteric or enterocolic fistula.

If an ileostomy or colostomy is necessary, study of the distal colon is worthwhile prior to ostomy takedown to ensure that no residual strictures exist.

Ischemic Colitis

Clinical

Bowel ischemia and various vasculitides are discussed in more detail in Chapter 17. Isolated colonic ischemia is relatively common, especially in the elderly, and its clinical and imaging manifestations are sufficiently discrete to warrant separate discussion. Colon ischemia is often included under the colitides. Especially when chronic in nature, ischemic colitis and some of the vasculitides tend to mimic inflammatory bowel disease. Some of the conditions associated with colonic ischemia are listed in Table 5.3.

A typical clinical presentation is sudden onset of abdominal pain, distention, and bloody maroon-colored diarrhea. Atypical presentations are relatively common; in a study of patients with eventually proven ischemic colitis, ischemia was initially not suspected clinically in 30% (82). Underlying atherosclerosis, shock, and congestive heart failure are common but not universal findings in these often elderly patients. Sequelae range from a mild, selflimiting condition to major bowel infarction and death.

Most common sites for colonic ischemia are at the splenic flexure and sigmoid.At the splenic flexure a branch of the middle colic artery forms an anastomosis with an ascending branch of the inferior mesenteric artery, feeding the marginal artery of Drummond. This marginal artery is present in less than half the population; the tenuous splenic flexure blood supply only becomes worse with onset of arteriosclerotic disease.